- Home

- Amanda Flower

Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3 Page 9

Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3 Read online

Page 9

Becky’s eyes watered. “Chloe, you could have been killed.”

And Bishop Glick would still be alive.

Becky shook her head and played with the end of her braid. “Chloe just moved here. No one would want to hurt her.”

I thought back to my encounter with Brock and his sidekick in the hospital parking lot. “There might be someone.”

Becky looked up, one eyebrow raised.

A grin formed on Chief Rose’s mouth. She leaned forward again and placed her elbows on her knees. I scooted my chair back an inch.

“Tell me who you suspect,” she said.

“It goes back to my first day in Knox County.” I told Chief Rose how Becky and I met and about my run-in with the two thugs in the hospital parking lot.

“Describe the men.” The chief removed a small notebook from her breast pocket and jotted down notes.

“One is thin, kind of wiry. They both had dark hair, but the wiry guy had a dirty blond goatee. The other one was clean shaven. He had the face of a twelve-year-old, but he was enormous. He looked like he could wrestle a bear to the ground if he ever had the need.”

Chief Rose smiled a little at the description.

“I know his name. The thin one called him Brock.”

“It must be Brock Buckley.” The police chief stopped just short of rubbing her hands together. “Your description fits him to a T. If it is Brock, dollars to donuts the other man is Curt Fanning.”

“Do you know them?” Becky asked.

“I’ve picked them up for disorderly conduct more times than I can count. Murder is new for them.”

I cocked my chin. “You think they meant to kill the bishop?”

“Not the bishop. You.”

My body began to shake the way it did whenever I had to speak in front a large group of people—a constant, full body shiver. I tensed my muscles in an effort to make the shaking stop, but it didn’t help. I prayed, too, needing to be in control. Disorderly conduct and harassing Becky was one thing . . . but murder?

Chief Rose leaned back in the armchair. “They have a well-earned reputation in the county, but let’s not jump to conclusions. We need a positive ID before we move forward.”

She stared at me until I broke eye contact.

“I need you to come to my station and view some photos.”

“Is it very far?” I held up Pepper as evidence. “I don’t have a car anymore, remember?”

She shook her head. “The police station is in the city hall building right on the square.”

Easy walking distance. “Sure,” I said.

“Great.” A smug smile played on Chief Rose’s lips. “I can take you there.”

I bit the inside of my lip. “Okay.”

“Can I go with her?” Becky asked.

The chief shook her head. “No. I might need you to ID these men later, but I’d like Chloe to make a positive ID all by herself first.” She stood. “Are you ready, Chloe?”

“Right now?”

“Yes, right now. The sooner you make the ID, the sooner I can bring them in.”

I took another breath and let it go. “Okay. I’m ready.” The shivering stopped, but the fear lingered.

Chapter Sixteen

It was Saturday, market day in Appleseed Creek. Buggies surrounded the town square, and Amish women sold homemade bread, canned jams and jellies, and fresh produce to their English neighbors and visitors. Chief Rose’s police car idled as a tour bus unloaded thirty elderly tourists in the middle of the street.

“I hate market day,” the police chief said.

Finally, the bus was emptied of passengers, and Chief Rose whooped her siren as she cut around it. She turned off the square and made an immediate left into an alley behind the town hall, a two-story, tan brick building with a rooster weathervane on top. There was a small patch of grass, maybe three feet wide, between the building and the road with a flagpole sticking out of it. Red geraniums decorated white boxes below first-floor windows. The American and Ohio flags flapped in the light breeze. A handful of cotton-like clouds bounced across an otherwise clear, blue sky. The weatherman had been right—it was cooler than the day before.

Chief Rose parked in the spot labeled “Chief.” From the parking lot, two doors led into the building, each labeled with forest green lettering. One read, CITY OFFICES, and the other, VILLAGE POLICE. So is Appleseed Creek a city or a village?

The chief unlocked the village police door and flicked on the lights. A scarred-up metal desk sat in the corner of the waiting room with a ten-year-old CPU monitor and computer on it next to a solid black telephone, circa 1980. A door in the middle of the back wall was flanked by windows on either side, their vertical blinds drawn. Wooden folding chairs lined the walls. Not much of an office. Where are the other officers?

“We share a 911 system with the city of Mount Vernon.” Chief Rose spoke as if reading my mind. “If it’s minor enough, we respond; if not, we call on Mount Vernon or the Knox County sheriff’s department for support. If it has something to do with Harshberger College, which most of our calls do, we work in conjunction with campus security.”

She used the royal “we” even though she was the only one here.

She stopped and regarded me. “I have two officers, in case you’re wondering, but they are both busy today keeping an eye on the farmers’ market. It’s always good to have a police presence there. You never know when city folk are going to put up a fight over the price of watermelon.” She kept a straight face when she said that.

The chief sorted through her key ring, found what she needed, and unlocked the second door, which opened into a meeting room. A long cafeteria-type table sat in the middle of the room surrounded by more wooden folding chairs. “Have a seat. I’ll grab the photos.”

I sat, careful not to pinch myself on the chair. The chief unlocked a third door and slipped through, closing it behind her before I could see inside. Seconds later she returned, carrying a three-inch black binder.

She sat catty-corner from me at the table and placed the binder on the table. “How’s Becky doing?”

“She’s upset.” I stopped myself from telling her what a stupid question that was. How does the chief think Becky is?

“She seemed better this morning than I expected her to.”

My brow wrinkled.

“I assumed she would be more upset, considering her relationship with Isaac Glick.”

“I thought I came here to check photos, not to talk about how Becky is doing. If you wanted to do that, why didn’t you ask her when you were at my house?” I frowned. “How would you know about Becky and Bishop Glick’s son anyway?” I moved my seat a few inches back from the table.

“The Amish aren’t as closemouthed as some would think.” She tapped the cover of the binder with blunt, clear-polished nails. “There are other complications too, of course. Becky’s father could lose his chance to be a preacher. His grasp was already tentative with his two oldest children leaving the Amish life behind. Now, the Troyer family will always be associated with the death of a beloved bishop.”

“What about the recent harassment of the Amish?” I asked. “The shotgun fire? The destruction of crops?”

She raised one eyebrow. “How do you know about that?”

“I heard the Troyer family discussing it, and I asked Timothy about it.”

“For being here less than two weeks, you’ve gotten a lot closer to them than I ever have.”

I remained steadfast. “What are you doing about the problems?”

She scowled and blew out a long breath. “Everything I can. It’s hard to investigate the case when none of the witnesses will tell you what they saw. They are too busy ‘turning the other cheek’ to talk to me.”

“But it could be related, right?”

&

nbsp; “Look at you. You’re like the Pippi Longstocking version of Nancy Drew.”

I slapped both hands on the table. “Chief Rose, you came to my house this morning and basically told me that someone tried to kill me. Is it any surprise that I would have questions?”

Her brows arched over her peridot-colored eyes. “Maybe I’ve been dealing with the Amish too long to know how a big-city girl like you would react.”

“May I see the photographs, please?” I reached out my hand.

She shrugged and slid the binder in front of me. “This is a book of thirty eight-by-ten mug shots. Look at each photo carefully. If you recognize one or both of the men who threatened you and Becky, let me know.”

I opened the binder. The first photograph was a man with a blunt nose and a horizontal scar across his right cheek. I wondered if he moonlighted as a pirate. The next photo held the likeness of a glaring man with huge ears. Each picture was scarier than the last. I glanced up at Chief Rose. “Do all these guys live in Appleseed Creek?”

She didn’t answer my question, so I flipped to the next page. Brock’s dark eyes stared at me. I knew him right away. Even in the mug shot he looked like a giant teddy bear, which he was not. “This one,” I said. “This is the one called Brock.”

She made a note in the spiral notebook in front of her. “Keep going.”

I was a bit disappointed with her reaction but moved on. Three ugly mugs later, I reached the end of the notebook and viewed the last photograph—Brock’s friend. I’d know that dirty goatee anywhere. “This is the other one.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

“You are positive on IDs?”

“Yes.”

She studied me with her disquieting green eyes for a long moment. Finally, she sat back. “You ID’d Brock Buckley and Curt Fanning, just as I thought.” She tapped her index finger on the dirty goatee guy’s nose. “Curt Fanning.” She flipped back through the binder and came to Brock’s photograph. “Brock Buckley.”

For some reason, knowing their names gave me courage. As unknown men in the green pickup, they were terrifying, but now that they were Brock Buckley and Curt Fanning—real people however unsavory—they were just scary.

The chief closed the binder. “We’ll pick them up and bring them in for questioning.” She slipped her hand into the breast pocket of her uniform, removed a business card, and placed it on the table in front of me. “If you see them again, or if they approach you, or even if you see their truck on your street, call me.”

I examined the card, embossed with the Appleseed Creek seal. It listed Chief Rose’s name, phone numbers, and address. “Shouldn’t I just call 911?” I tapped the card on the table before dropping it into my purse.

“If you feel you are or someone else is in danger, by all means dial 911, but in any other case, call me.” She stood. “I’ll give you a ride back home.”

I shook my head. “I’d rather walk.” The Pippi Longstocking comment still annoyed me.

She shrugged.

Before I left the room, the chief said, “I forgot to tell you, welcome to Appleseed Creek.”

I glanced back at her, and she smiled. Only it didn’t reach her eyes.

Chapter Seventeen

Instead of walking around the Amish farmers’ market, I decided to go through it. The more people around, the safer I would feel. Besides, if I brought home some fresh fruit, it might cheer up Becky. I kept my eye out for Curt and Brock. Part of me expected them to jump out from behind one of the buggies parked around the square.

I meandered near three young women sitting at a table of pies and staring at me. As I passed, I heard whispering but tried to think nothing of it. The acknowledgment that someone had deliberately tried to cause me harm—a.k.a. kill me—left a burning in my stomach and a trembling in my body that I couldn’t completely control.

The fruit stand sat in the middle of the square by the town’s fountain, which had a bronze replica of Johnny Appleseed leaning against an apple tree in it. A mischievous grin marked the statue’s face. Dozens of donor names were chiseled into the cement wall encircling the fountain.

I picked up a green quart container of strawberries. Becky would be able to make a pie with them. “How much for the strawberries?” I asked the fruit seller, an Amish girl who was no more than fifteen.

The Amish girl scowled. “Two dollars.”

“I’ll take them.”

Gruffly, she took the strawberries from my hand and dumped them into a plastic shopping bag. I handed her the money.

A middle-aged Amish woman marched to the girl’s side and said something in their language. The girl hung her head and put the strawberries back into the green carton while the older woman removed my two dollars from the money pouch sitting on the table. “Here is your money.”

I didn’t take the bills. “Is something wrong?”

She tried to force the money back into my hands.

“What about the strawberries?”

Her eyes narrowed. “We cannot sell to you.”

When I wouldn’t take the money, she placed it on the table in front of me. “What do you mean?”

The younger Amish woman replied in their language, but the only word I understood was “Glick.” My stomach dropped. This was about Bishop Glick and Becky. I stepped away from them and left the money on the table. Part of me wanted to scream for this injustice against Becky, and reveal that my brake line had been cut, but my saner, calmer side prevailed. I bit back the retorts that would only spread more gossip through the district.

I felt the eyes of the Amish watching me as I wove around the booths and card tables. Not until I turned the corner on Grover Lane did I let out a sigh of relief. If the Amish treat me this way, how will they treat Becky?

At the house, Becky sat on a brown folding chair on our rickety front porch. Gig was in her lap, purring. Since the house faced east, the morning light leaked though holes in the porch’s roof and reflected off of her white-blonde hair, giving her an otherworldly halo.

When she saw me, she jumped up from the chair. Gigabyte hung from her unbroken arm and yowled, so Becky opened the front door and placed the cat inside. “Chloe, I have great news!”

I blinked. “You do?”

She hopped from foot to foot. “Remember, I told you about Cookie and Scotch last night?”

I climbed the last step to the porch. “Yes.”

“They own Little Owl Greenhouse, and I called Cookie this morning. She offered me a job!”

I leaned against the post. It shifted under my weight, and I shuffled away. Probably a good thing Timothy planned to mend it. “She gave you a job over the phone?”

“Yes. I start Monday!”

“Without an interview?”

“Cookie said she didn’t need to interview me because I was so responsible for calling her right away. She knew I would be perfect for the greenhouse.”

My forehead wrinkled. “Do you know anything about plants?”

“Of course. My family has a huge garden.”

I paused. “Are the plants the greenhouse sells different from those in an Amish garden?”

Her face fell. “I thought you’d be happy.”

“Becky, I am happy, but I’m surprised too. Where is the greenhouse?”

“Just off”—she paused—“Butler Road.”

I inhaled and glanced at the sky before bringing my gaze back to Becky. “How are you going to get there? We don’t have a car.”

Becky shifted from one foot to another. “I told Cookie that, and she and Scotch will drive me until you have a car again.”

I mulled that one over. “That’s awfully nice of them.”

“They live near the square too, so they don’t have to go out of their way or anything.

”

I pointed at her cast. “Did you tell them about your arm?”

“Yes, but Cookie said there was plenty of other work for me to do.” She peered at me. “Isn’t this great?”

I nodded, still unsure. And yet, I too was hired over the phone.

Becky sat back down in her chair. “What happened at the police station?”

I relayed my visit to the police station, but decided not to mention the incident at the farmers’ market.

“Why didn’t you tell me about those men in the pickup?”

“I didn’t want to worry you.” Tentatively, until I knew it could hold my weight, I leaned on the crooked railing surrounding the porch. Sunshine warmed my back.

She frowned. “Why does everyone treat me like a child? Even you, Chloe.”

“We want to protect you.”

She took a deep breath and looked away. “What’s going to happen to me?”

“I don’t know.” I shifted to allow more sun onto my shoulders. “Can you tell me about the accident? I haven’t heard about it from you yet, at least not all of it.”

“I turned onto Butler Road and drove to the top of the hill. Everything was fine. I thought I would make it to the greenhouse and back before you got home from work.” Becky faced me again. “I wanted to surprise you with my new job.”

“How do you know how to drive a car?”

“Isaac has a license. He got it during his rumspringa. He’s always been fascinated with mechanical contraptions, so he took me out several times in his truck and taught me. I know we shouldn’t have been doing that. It was a secret we shared.”

I winced. Having been the one who taught Becky how to drive could only make the young Amish man feel worse. “Isaac is no longer in rumspringa?”

“No, he was baptized last spring.”

“What happened when you reached the top of the hill?”

“I wasn’t going fast, maybe thirty-five miles per hour. It’s steep there and the truck’s speed picked up fast. I tapped the brake to slow down and the pedal went all the way to the floor. By this time, the car was coasting at over fifty. I saw it on the numbers behind the steering wheel.”

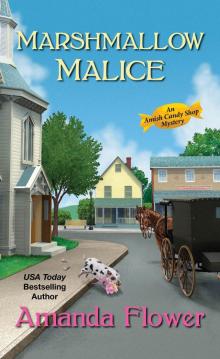

Marshmallow Malice

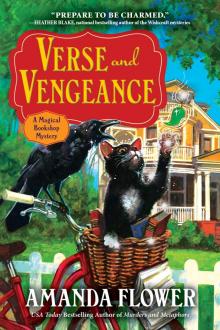

Marshmallow Malice Verse and Vengeance

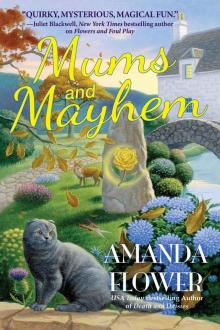

Verse and Vengeance Mums and Mayhem

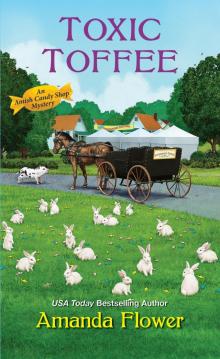

Mums and Mayhem Toxic Toffee

Toxic Toffee Criminally Cocoa

Criminally Cocoa Assaulted Caramel

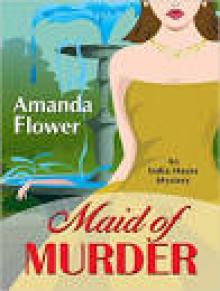

Assaulted Caramel Maid of Murder aihm-1

Maid of Murder aihm-1 Murders and Metaphors

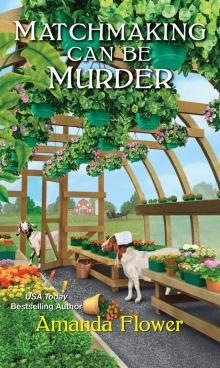

Murders and Metaphors Matchmaking Can Be Murder

Matchmaking Can Be Murder Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery)

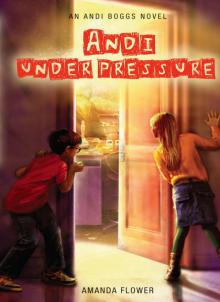

Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery) Andi Under Pressure

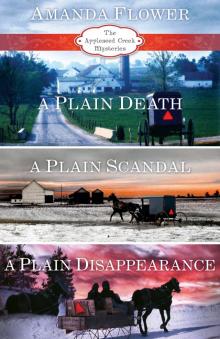

Andi Under Pressure Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3

Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3 A Plain Disappearance

A Plain Disappearance Andi Unstoppable

Andi Unstoppable The Final Vow

The Final Vow A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4)

A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4) The Final Tap

The Final Tap The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery

The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery Andi Unexpected

Andi Unexpected Lethal Licorice

Lethal Licorice Premeditated Peppermint

Premeditated Peppermint Death and Daisies

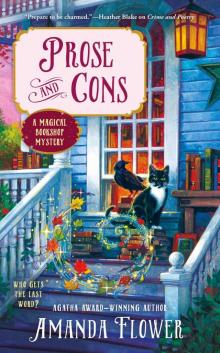

Death and Daisies Prose and Cons

Prose and Cons