- Home

- Amanda Flower

Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3 Page 10

Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3 Read online

Page 10

“The speedometer?”

She shrugged. “If that’s what you call it.” She closed her eyes and her voice shook. “I couldn’t stop. There were brambles along the road at the bottom where the road curves. I pointed the car at those, thinking they’d stop me.” She was silent, her eyes closed for a full minute. If I didn’t know better I would have thought she had dozed off.

I prodded her. “So you hit the brambles . . .”

She took a shuddering breath and opened her eyes. “No. As I got there, Bishop Glick’s buggy came around the bend in the road. I couldn’t do anything. There was no time to turn the car in another direction.”

Despite the warm sun on my back, a chill ran down my spine.

“I saw the horse first. I turned the steering wheel hard to the right to miss the animal, but by doing that I hit the buggy full on instead.” She rubbed her hands up and down her bare arms. Tears sprang to her eyes. “Bishop Glick recognized me. He saw it was me who hit him before he died.”

I walked over to her, knelt by the chair, and wrapped her in a hug.

“It’s my fault,” she whispered between sobs.

Her tears soaked through the shoulder of my yellow T-shirt. “You shouldn’t have been driving the car. You know that, but remember what the police chief said. Someone cut the brake line. You had nothing to do with that.”

She sat up and used the end of her long braid to dry her eyes. “Do you really think it was those men?”

I shook my head. “I don’t know.”

A hiccup escaped her. “What if it’s not? Who else could have done this?”

“I don’t know.”

“What’s going to happen to me?” She asked the question again, her voice an octave higher.

Again, I told her all that I really could at this point. “I don’t know.”

Chapter Eighteen

An hour later, Becky lay on the floor flipping through her sketchbook while I sat in the armchair and researched on my iPad how someone could cut a car’s brake line. It was frighteningly easy. Through a simple search, I obtained step-by-step instructions with pictures.

The article I read claimed that a brake warning light would be illuminated on the car’s dash. “Becky, did you see any strange lights glowing on the front of the car near the place you watch your speed?”

She looked up from her sketchbook. “I don’t think so.”

“It would have said ‘brake.’”

She shook her head and I repressed a sigh. Would I have noticed the brake light either? Probably. I doubted Becky was familiar enough with a car’s dashboard to notice something was wrong. She didn’t even know the word “speedometer.”

A clack, clack, clack came from outside. I closed the cover to my iPad and looked toward the door.

“It sounds like a buggy.” Becky hurried to the window. “Grossdaddi and the kinner are here!” Some of the music had returned to her voice. She threw open the door and disappeared outside.

I followed her.

“Gude mariye!” Grandfather Zook grinned from his perch at the front of his glossy black six-seater buggy. The three younger Troyer children waved from the back. “Get in!” he said. “We’re going to Young’s Flea Market!”

Becky shook her head so hard I was afraid she’d give herself a crick in her neck. “Grossdaddi, I can’t go to Young’s.”

Grandfather Zook cocked his head. “Why not?”

Becky looked up, and tears welled in her eyes.

“Come here,” her grandfather said.

Becky moped around the side of the buggy. Grandfather Zook placed his hand on her head and leaned down, whispering to her.

His horse nudged me in the shoulder and snorted. He was a beautiful, dark brown, lean animal with a white star in the middle of his forehead. Thomas climbed over his sisters and hopped out of the buggy. “That’s Sparky.”

I scratched the horse’s star. “Sparky? That doesn’t seem like an Amish name.”

“That’s the name he came with. He’s a racehorse,” he said proudly. “He’s the fastest horse in Knox County. We can get places in half the time it takes most folks.”

Grandfather Zook squeezed Becky’s shoulder. “Sparky’s a retired racehorse and not as fast as he used to be. His full name is Sir Sparkalot Lightning March.”

“That’s quite a name.”

“Sparky sounds better,” Thomas declared.

Sparky’s ear flicked back and forth as if he listened to the conversation.

“Old Spark doesn’t like it when I say he’s slowed up,” Grandfather Zook said. “He’s plenty fast for us. Any faster and we’d be breaking the speed limit. I’d hate to be pulled over by the coppers.”

My jaw dropped. “The police pull over Amish buggies?”

Grandfather Zook laughed. I liked the sound of it. It was a rumble that came up from deep inside and shook his whole body, making his long white beard wave back and forth like a flag. What would my life have been like if I’d had a grandfather? My mother’s parents both died long before I was born, and my father was estranged from his mother and father. His mother is gone now, and if I tried to find my grandfather, my father would be furious. Sabrina wouldn’t be too happy about it either, but then again, nothing I did made Sabrina happy.

“I bought him from a thoroughbred breeder two years ago.” Grandfather Zook moved the reins from hand to hand. “Lots of Amish carriage horses are retired thoroughbreds. We can give them a quiet retirement, and what horse wouldn’t want to be trotting around the countryside pulling a sharp-looking buggy like mine?”

“Can we go now?” Ruth asked. “Anna Lambright is waiting for me at the market.”

“You girls run back into the house and grab the things you need for the day,” Grandfather Zook shooed us on, not taking no for an answer.

Despite the humid air, Becky wrapped her good arm around her shoulder as if she felt a chill. “Why do you want to take us to the flea market, Grossdaddi?”

“We need to find you kinner some furniture. You said at supper yesterday that you have one chair between you.” He tsked. “The flea market is the best place to find everything you need, especially if I’m at your side.”

Cheer returned to Becky’s face. “Grossdaddi can talk a fat man out of his fry pie.”

Thomas giggled.

Ruth jumped from foot to foot. “Can we go now, please?”

Becky looked up at her grandfather. “Grossdaddi, I don’t want to go there. Not after what I did . . .”

“Ya, you made a mistake, but you cannot hide. That will just make folks talk more. If you look them in the eye, they might think twice before they say something.”

Or, I thought, if you’re dealing with someone like Sabrina, she’ll just insult you to your face. It was difficult for me to imagine anyone like my stepmother among the Amish.

Becky considered me. “What do you think, Chloe?”

I observed the sky, bright blue and clear. A sky I wasn’t used to. Rarely was there a clear sky like this one in Cleveland on the banks of Lake Erie. Instead, huge clouds rolled off the great lake and hung overtop the city. Today was a perfect day for a buggy ride. “We could use another chair or two.” I scratched Sparky behind the ear. And I could get out of the house and stop obsessing over the accident.

Becky smiled just a little. “I am tired of sitting on the floor.”

Grandfather Zook grinned. “No more talk, then. Into the buggy with the both of you.”

Ten minutes later, Becky sat in the back of the buggy in between Thomas and Ruth, and I sat in the front next to Grandfather Zook with Naomi on my lap clutching her doll.

Grandfather made a clicking sound with his tongue. “Head ’em up, Sparky.”

I grinned. “Head ’em up?” Amish meets Old West?

He winked at me.

The black paint inside the buggy was polished to such a high sheen that I saw my reflection in the ceiling. Everything was spotless, even the high-gloss floorboards. “Your buggy’s beautiful,” I told Grandfather Zook.

“It better be,” Thomas said from the back row. “Grossdaddi has me polish it once a week.”

“I pay you in candy.” Grandfather Zook pretended to be offended.

The girls laughed, even Becky. Maybe Grandfather Zook was right and the trip to the flea market would lift her spirits.

Naomi held up her doll for me to see.

“She’s beautiful,” I said. “But where is her face?”

“Naomi doesn’t speak Englisch,” Thomas said. “She hasn’t started school yet.”

“Oh.”

“Her doll doesn’t have a face because Daed says it’s wrong.”

I glanced at Grandfather Zook. “Wrong?”

“It makes a craven image,” Thomas said.

Ruth snorted. “Graven image, you goof.”

Thomas made a face at his sister.

“That’s why Daed and Becky fight. Becky draws people with faces,” Ruth said.

I glanced back at Becky, and a grim line crossed her delicate face. She wouldn’t meet my gaze.

Naomi looked up at me with huge blue eyes, her forehead creased.

“She’s a lovely doll with or without a face.”

She smiled and snuggled into my lap.

Grandfather Zook flicked the reins, and Sparky stepped away from the curb. “Enough talk about dolls. Off to the flea market, but first we must swing by Timothy’s.”

I told the butterflies in my stomach to be quiet. “Timothy?” My voice squeaked.

A wide smile spread across Grandfather Zook’s face, and I felt my own turn red. Was I that obvious? Thankfully, the children didn’t seem to notice.

“Oh, yes, I want all my grandkinner on this trip,” Grandfather Zook said.

“Yea, Timothy!” Thomas shouted from the back row.

“Yea, Timothy!” Naomi agreed on my lap.

Yea, Timothy, my heart whispered.

Chapter Nineteen

As Grandfather Zook drove the buggy through the neighborhood, neighbors peeked out of their windows to catch a glimpse. Yet no one seemed surprised to see an Amish buggy rolling down their street. This was an everyday event in Appleseed Creek. I tried to imagine what would happen if a buggy turned into the Greens’ cul-de-sac in Shaker Heights. I smiled at the image. Hopefully, Grandfather Zook didn’t think I was smiling because of Timothy.

“Do you have other grandchildren?” I asked.

“Oh yes, I have.” He thought for a minute. “Thirty-two back in Lancaster.”

My mouth fell open. “Thirty-two!”

His beard waved with a chuckle. “And eight, almost nine, great-grandchildren.”

“Wow.”

“Do you have any brothers and sisters, Chloe?” Ruth asked. She leaned forward and folded her thin arms over the front seat.

“I have a younger brother and sister. They live in California.”

“California!” Ruth cried. “I’d love to go there. I want to see the ocean.”

“Don’t let your daed hear you say that,” Grandfather Zook teased. “He’d have a heart attack.”

“Anna Lambright saw the ocean. Her whole family did. They took the bus to Florida two years ago. She said it was the best place in the world and what heaven must be like.”

Becky barked a laugh. “Until she stepped on the jellyfish. She wasn’t too keen on the ocean after that.”

Ruth fell back into her seat and crossed her arms over her chest. “I still want to see it.”

“If you want to see it someday, Ruthie, I’m sure you will.” Grandfather Zook spoke in a soothing voice.

Sparky turned a corner, and the low limbs of a buckeye tree grazed the top of the buggy.

“Sparky,” Grandfather Zook reprimanded. “Watch the paint job.”

I laughed.

“There’s Timothy’s house,” Thomas cried. He pointed at a large Victorian home three driveways down, its exterior walls lavender with dark purple shutters. It seemed like a strange place for guys to live, especially former Amish guys.

A young man in a brown plaid short-sleeve shirt and cargo shorts dribbled a basketball on the asphalt driveway. When the buggy parked in front of the purple Victorian, he stopped playing and tucked the basketball under his arm. “Yo, Tim! Your family is here.”

Ruth leaned forward in her seat again. “That’s Danny Lapp.”

“Ruthie has a crush on Danny,” Becky said.

“I do not,” Ruth hissed.

Danny sauntered over to the buggy with the basketball still under his arm.

“Want to come to the flea market with us today, Danny?” Grandfather Zook asked.

“No, thanks, I have a job over in Fredericktown this afternoon.” He smiled at me. “You must be Chloe. I’ve heard a lot about you.”

I felt myself blush. Did Timothy talk about me? “Nice to meet you.”

Timothy stepped out the front door and jumped down the steps. “Gude mariye. Ready to go furniture shopping?” he asked me with twinkling eyes.

“Yes.” My voice still squeaked.

Danny and Grandfather Zook shared a grin.

Timothy didn’t seem to notice. “If we buy anything, there won’t be any room in the buggy to bring it home. I’ll take my truck. Anyone want to ride with me?”

“I do!” Ruth and Thomas both clamored at the same time to ride with Timothy.

Grandfather Zook waited for Timothy to start his pickup before he flicked the reins on his buggy. “I think it’s only fair to give Timothy a head start.” He chuckled.

Sparky wove through the narrow one-way brick streets surrounding the square as the Amish selling their wares were packing up for the day. Behind me, Becky put her head down. The two Amish women who refused to sell me the strawberries stared at us as we trotted past.

Soon the houses and gas stations gave way to open farmland. In the distance, half a dozen Amish children ran around a yard as their mother sat on a stool shucking corn. If it had not been for the electric posts taking power back to the small town of Appleseed Creek, I would have thought I had wandered into the nineteenth century. Does it look like the nineteenth century to Becky and her family? Or is this normal?

Sparky rocked his head back and forth.

“Stop preening, Sparky.” Grandfather Zook glanced at me. “He’s such a showboat. Thinks he’s the most attractive horse in the county.”

“He is the most handsome horse in the county,” Becky said, coming to Sparky’s defense.

Sparky wiggled his ears, and Naomi, now curled up on Becky’s lap in the backseat, laughed.

I moved my foot and knocked Grandfather Zook’s crutches that were tucked under the front bench seat. “I’m sorry.”

He glanced down. “Don’t worry about those old things. They are built to last. You wouldn’t believe how many times I’ve dropped them off the buggy.”

“Why do you need them?” As soon as it came out of my mouth, I regretted my question.

Grandfather Zook smiled. “I had polio when I was a child.”

“Oh. You weren’t vaccinated?” I squirmed. “I’m sorry. That’s a personal question.”

He laughed. “I’m glad you think I’m that young, but I had polio long before the vaccine was out. I made sure my daughter had all my grandkinner vaccinated. It took some convincing for my son-in-law to agree.”

“The Amish usually don’t vaccinate their children?”

“There are no rules against it, but many times they don’t because they don’t know any better. I do, so I insis

ted.”

I thought about that as we fell into a peaceful silence. For the next thirty minutes, the only sounds were the clomp, clomp of Sparky’s hooves on the pavement and the rattle of the buggy.

I shifted as my back began to ache from leaning against the hard wooden seat. No one else seemed to be uncomfortable, not even Grandfather Zook.

“Almost there.” Becky pointed to a line of buggies and cars that appeared on the side of the road. “They are all here for the flea market. People, Englisch and Amish, come from all over.”

“Best sales in the county,” Grandfather Zook declared. “Parking lot must be full. Not to worry, though, I always have a place to park.”

“Ellie Young lets Grossdaddi park the buggy behind the restaurant. She won’t let anyone else park there.” Becky laughed. “Ellie Young’s a widow and has eyes for Grossdaddi.”

Grandfather Zook snorted. “Your grossmammi and Ellie were freinden. Grossmammi asked Ellie to look after me after she was gone. That’s the end of that.”

“Ellie takes her job seriously,” Becky said in a mock somber tone.

Grandfather Zook’s grinning face reflected in the buggy’s glossy dash.

We passed buggies of all shapes and sizes. Some had orange triangles on the back, others had headlights and taillights, and still others had simple white strips of reflective tape. I’d never noticed the variation before. “The buggies aren’t identical,” I said. “I thought they would be. Some have headlights.”

“Mine has headlights too.” He pointed to the switch on the dash. “The bishop permitted battery-operated headlights in our district.”

“That’s allowed?”

“It’s for safety,” he said. “You can tell by the buggy what type of Amish it is. Most of the folks around here are Old Order, like us, but there are a few Swartentruber Amish. They are the strictest. Those are the buggies without the SMV, or slow moving vehicle, triangles. They are also the ones you see selling baskets on the side of the road. They rarely work outside of the farm. For instance, they wouldn’t run any of the shops in town,” Grandfather Zook explained.

Marshmallow Malice

Marshmallow Malice Verse and Vengeance

Verse and Vengeance Mums and Mayhem

Mums and Mayhem Toxic Toffee

Toxic Toffee Criminally Cocoa

Criminally Cocoa Assaulted Caramel

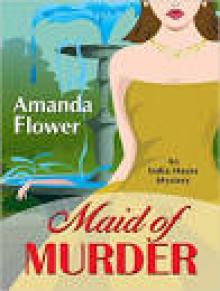

Assaulted Caramel Maid of Murder aihm-1

Maid of Murder aihm-1 Murders and Metaphors

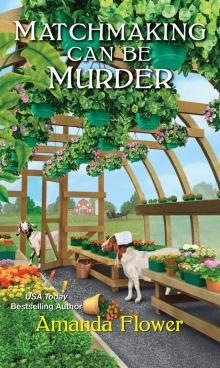

Murders and Metaphors Matchmaking Can Be Murder

Matchmaking Can Be Murder Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery)

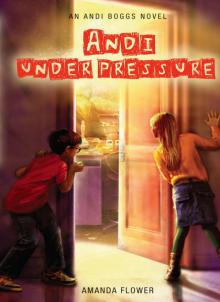

Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery) Andi Under Pressure

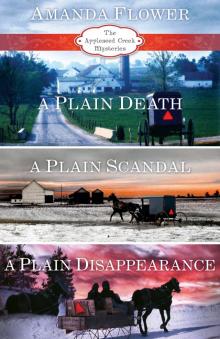

Andi Under Pressure Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3

Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3 A Plain Disappearance

A Plain Disappearance Andi Unstoppable

Andi Unstoppable The Final Vow

The Final Vow A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4)

A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4) The Final Tap

The Final Tap The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery

The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery Andi Unexpected

Andi Unexpected Lethal Licorice

Lethal Licorice Premeditated Peppermint

Premeditated Peppermint Death and Daisies

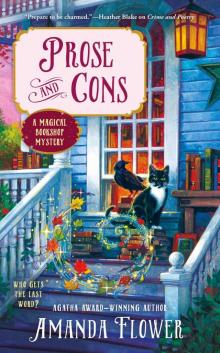

Death and Daisies Prose and Cons

Prose and Cons