- Home

- Amanda Flower

The Final Tap

The Final Tap Read online

Copyright Information

The Final Tap: A Living History Museum Mystery © 2016 by Amanda Flower.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any matter whatsoever, including Internet usage, without written permission from Midnight Ink, except in the form of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

As the purchaser of this ebook, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. The text may not be otherwise reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or recorded on any other storage device in any form or by any means.

Any unauthorized usage of the text without express written permission of the publisher is a violation of the author’s copyright and is illegal and punishable by law.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

First e-book edition © 2016

E-book ISBN: 9780738748108

Book format by Teresa Pojar

Cover design by Kevin R. Brown

Cover illustration by Tom Jester/Jennifer Vaughn Artist Agency

Map by Llewellyn Art Department

Midnight Ink is an imprint of Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Flower, Amanda, author.

Title: The final tap / Amanda Flower.

Description: First edition. | Woodbury, Minnesota : Midnight Ink, [2016] |

Series: A living history museum mystery ; 2

Identifiers: LCCN 2015049002 (print) | LCCN 2016002421 (ebook) | ISBN

9780738745138 (softcover) | ISBN 9780738748108 ()

Subjects: LCSH: Murder--Investigation--Fiction. | Maple sugar

industry--Fiction. | GSAFD: Mystery fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3606.L683 F565 2016 (print) | LCC PS3606.L683 (ebook) |

DDC 813/.6--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015049002

Midnight Ink does not participate in, endorse, or have any authority or responsibility concerning private business arrangements between our authors and the public.

Any Internet references contained in this work are current at publication time, but the publisher cannot guarantee that a specific reference will continue or be maintained. Please refer to the publisher’s website for links to current author websites.

Midnight Ink

Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

2143 Wooddale Drive

Woodbury, MN 55125

www.midnightinkbooks.com

Manufactured in the United States of America

For Molly and Samantha

He should be as vigorous as a sugar maple, with sap enough to

maintain his own verdure, beside what runs into the troughs, and not like a vine, which being cut in the spring bears no fruit, but bleeds to death in the endeavor to heal its wounds.

–Henry David Thoreau

One

Part of my life is stuck in 1863, and I’m starting to realize that might be a dangerous place to live. The thought struck me in the early morning while standing in the sugar maple grove on the west edge of Barton Farm’s grounds as my toes curled in from the cold despite two pairs of woolen socks and sturdy snow boots. It wasn’t so much the cold that made me question my life; it was the large man standing a few feet in front of me brandishing a hand drill as if it were a bayonet.

I held up my hands. “Dr. Beeson, if you put the drill down, I’m happy to listen to whatever it is you have to say, but if you continue to wave it back and forth, our conversation is over.”

He glanced down at the drill in his hand and scowled as if he were seeing it for the first time. With a grunt, he dropped it to his side. “How am I supposed to teach the tree tapping class tomorrow if I cannot tap the trees? They’re frozen solid.”

It had been an unseasonably cold winter in northeastern Ohio, and even though it was the first week of March, the high temperature still hovered in the twenties. The weatherman had made some murmuring about a break in the weather by midafternoon, but he’d said it with some trepidation. He probably feared for his life if his prediction turned out to be wrong. Staring at Dr. Conrad Beeson and his drill, I could relate. Beeson was a large man, well over six feet and likely to tip the scale at three hundred pounds. He wore black-rimmed glasses and had a full beard that he kept neatly trimmed.

He held the drill up again. “And why on earth do I have to use this antiquated tool? Everyone who taps trees uses a power drill today.”

My tan and white corgi, Tiffin, stood at attention, ready to defend me if the need arose. His soulful brown eyes were trained on Beeson’s drill.

I took a deep breath. “I understand that, but we would like at least part of the demonstration to be authentic to what tree tapping was like back during the Civil War in Ohio, which our farm and village strives to represent.”

He opened his mouth as if he was about to argue the point some more, but I was quicker. “I can understand your frustration, but I have no control over the weather.” I did my best to keep my voice even. It was a bit of a struggle. The good doctor was wearing on my last nerve. I sorely regretted including a tapping presentation to kick off Barton Farm’s Maple Sugar Festival, a new weekend event on the Farm that I hoped would become an annual tradition and earn some much-needed revenue. During the quiet winter months, the money-making half of Barton Farm—the historical village across Maple Grove Lane—was closed.

“You have to think of something,” he protested. “I can’t be expected to work under these conditions.”

“We could always wrap electric blankets around the tree trunks to heat up the sap. Would that help?” Benji Thorn, my new assistant, asked. She stood beside me with her hands deep inside the pockets of her down coat. Benji was new to the position, but she wasn’t new to Barton Farm. Now in her senior year of college, she’d worked at the Farm every summer since high school as a historical interpreter.

I shot Benji a so-not-helping look.

She grinned and, unpocketing a mitten, casually flipped one of her many dark braids over her shoulder.

Beeson glared at her. “I don’t appreciate your sarcasm, young lady. This is a serious issue. If there’s no sap, there can be no class.”

“Now wait,” I said, holding up my hands. “We can still have your presentation in the visitor center, and you can still demonstrate how to tap a tree. I’m sure the class will be understanding about the weather. We have thirty people registered, and they’re enthusiastic to hear what you have to say about the history of maple sugaring and possible techniques they can use on their own trees.”

He scowled. “What is the point of fake-tapping a tree?”

“This is supposed to be educational, Dr. Beeson. I thought that as a college professor, you would recognize that,” I said.

“I’m a professor of horticulture and work for the college, but I’m mainly a researcher. I’m not trapped in a classroom all the time with undergraduates who would much rather be twittering each other than learning how to care for plants.”

Benji covered a snort with a cough when he said “twittering.”

It didn’t seem like Beeson missed Benji’s snort. The maple sugar expert sniffed. “This is a waste of time, and certainly not worth the measly honorarium you’ve offered to pay me. I would be better off preparing for my own maple sugar season. Because of the weather, it’s going to be late this

year. When that happens, the season is usually short. You have to extract the sap from the trees when the trees are ready. When the sap stops running, it stops. There’s nothing that can be done about that.”

I counted to ten, backward, to stop myself from saying something I might regret or something that would make Beeson quit the Maple Sugar Festival altogether. There wasn’t enough time to find a replacement instructor for the tree tapping class; I’d already scrambled to find Beeson when my first expert had backed out. I had things to do—three school buses of third and fourth graders from New Hartford Elementary School were bound for the Farm at that very minute. My director of education had devised a school program to tie in with the Maple Sugar Festival, and I needed to return to the visitor center to greet the children.

“Hey,” Benji said, narrowing her dark eyes. “You should be happy Kelsey invited you here to speak. It’s a huge event for the Farm, and we already have over a hundred people registered for Saturday and Sunday, not to mention the thirty coming tomorrow for your course. You should be happy with the publicity the Farm is giving you and your book. Kelsey’s letting you sell books after the class and during the festival. You can make money off of that.”

Benji wasn’t a count-to-ten-backward kind of girl.

The book Benji was referring to was Maple Sugar and the Civil War, Beeson’s scholarly text that had been released a few weeks earlier. During the Civil War, maple sugar was a hot commodity in the north, since after the south ceded from the Union, sugar cane and molasses were hard to come by. In its place, the northerners used maple syrup to sweeten their coffee and to bake with. So when I’d needed to quickly find a new instructor for the tree tapping class, I’d thought Beeson was the ideal candidate—his book fit perfectly with our Maple Sugar Festival, especially since I’d have a small group of Civil War reenactors on the Farm grounds during the festival.

It appeared that I might have been wrong.

Beeson glared at Benji and then at me. “How dare you let your employee talk to me in such a manner!”

I held up my hands again. My fingers stung from the cold despite the two heavy pairs of wool gloves I wore. “Now that we’ve checked on the trees, I think it would be best if we returned to the visitor center to discuss this further. It’s far too cold out here to argue.”

“If it’s too cold to be outside, it’s too cold for sugaring,” he said before stomping down the pebbled path in the direction of the visitor center.

After the professor disappeared, Tiffin relaxed and started sniffing the bases of the many maple trees in the grove. The land that became Barton Farm had been purchased by Jebidiah Barton around the turn of the nineteenth century. There were already maple trees there when he arrived, but in 1820 he began planting more, with the intention of starting up a maple syrup business.

It was one of the many farming endeavors the Barton family tried over the years to keep their farm profitable. They were also known for their livestock and their beekeeping. When the trains made it to the northeast corner of Ohio, Jebidiah and his son started shipping their honey and maple syrup back East to their home state of Connecticut. This went on for five generations. Eventually, the last of the Bartons’ living relatives willed that the Farm be turned into a museum to preserve local history and teach the community, especially the children, what it was like in pioneer days in Ohio. That happened in 1964; it wasn’t until the Cherry Foundation donated the money to renovate the buildings and grounds that the Farm actually became a museum. I was the second director of Barton Farm, and the first one to live on the grounds year-round.

“Can you please try to play nice with Dr. Beeson?” I asked Benji.

She folded her arms. “He’s a pompous jerk. Just because he has a doctorate in maple sugar doesn’t mean he can speak to you like that.”

I hid a smile. “I don’t think you can have a PhD in maple sugar. His degree is in horticulture, and we’re lucky to have him for this event, especially on such short notice. His book really illustrates the history we’re sharing with the community this weekend.” After the festival opened on Friday with the tree tapping class, it would get into full swing over the next two days with pancake breakfasts, maple sugaring demonstrations, and the reenactors talking about the importance of maple sugar during the Civil War.

Benji snorted. “He should be thanking you for hiring him at all. We’re certainly paying him more than he deserves. I can’t believe he questioned his honorarium. It’s not like he came from out of state. He’s not even coming from out of town. He lives right here in New Hartford.”

She had a point. Beeson’s speaking fee was higher than I’d expected, but when the original expert was struck down by a mysterious illness and landed in the hospital, I couldn’t quibble over details. Of course, I’d thought Beeson was the perfect replacement instructor. And as mentioned, I’d been wrong.

“Can you try to be nice?” I asked. “After Sunday, this will all be over. We can always find a different person to teach the tree tapping class next year if he doesn’t work out. We have a whole year to plan.”

She grunted. “All right, but it’s for you, not for him.”

“That’s fine with me.” I smiled and stomped my numb feet. “Now let’s head back to the visitor center. If we stay out here much longer my toes are going to freeze off.”

“Mine already have,” she said with a sigh.

two

Despite her lack of working toes, Benji and I made it to the visitor center without incident. When I walked through the automatic glass doors that led into the building, Tiffin shot across the polished, pine-planked floor and curled up in his dog bed by the hearth. He gave a contented sigh as he rested his chin on his white paws and absorbed the warmth from the crackling fire.

I took a deep breath. The inside of the visitor center smelled like a combination of the fire, pancakes, and maple syrup. The school children who were coming to the Farm would be treated to pancakes, just like our guests would be during the festival.

Benji headed to the kitchen to check that Alice, our head cook, had everything under control for the children’s lunch.

Yesterday, the first day of the program, we’d hosted a group of fifteen homeschoolers. We had a few minor maple syrup spills on the dining room floor, but other than that, the day had been a great success. Tomorrow would be the third and final day of the school program, coinciding with the kick-off of the festival.

Because we didn’t yet have any maple sugar of our own to turn into syrup, we’d purchased some from a farm in Kentucky, where the sugaring season was already in full swing. I wished that we had our own sugar for the demonstrations, but we carried on with the Kentucky maple sugar because I believed it was important for the kids to see how the syrup was made. I’d sold the program to the local schools not only on the historical aspect the Farm always offered, but on the science too. Temperature control, evaporation, crystallization, and all of those scientific concepts were included in the creation of maple syrup.

As my director of education, Gavin Elliot was great with the kids, probably because he was much like a kid himself. It had been his idea to create the school program as a companion event to the Maple Sugar Festival. I was grateful to see that his idea seemed to be paying off.

Gavin was only a couple of years out of college and constantly being asked by guests what high school he went to. In protest against being mistaken for seventeen, he’d grown a full, dark beard not unlike Beeson’s. Now, instead of just looking like a teenager, he looked like a teenager dressed up like a lumberjack for Halloween. He finished the look with a red flannel shirt over his Farm polo and khaki pants.

“Is the sugarhouse ready for the kids?” I asked him.

He glanced over at me. “Hey, Kelsey. The sugarhouse is good to go. I’ve had the fire going for a couple of hours already and have the batch of maple sugar boiling at the right temperature.”

I glanced back through the window. The sugarhouse was an old, whitewashed building, a reconstruction of the sugarhouse the Bartons built on the same spot in 1820. The original building had burned to the ground sometime during the Great Depression.

Smoke rolled out of the sugarhouse’s chimney. I hoped to have time to peek inside soon and see Gavin’s presentation with the kids, but first I had to find Beeson. “Did Dr. Beeson come in here?” I asked.

“I haven’t seen him.” Gavin frowned. “I don’t know why you picked him as the replacement. I could have done it. I’m the one talking to the kids for the maple sugar program, and the lecture isn’t that different. My father taps more trees than anyone else in New Hartford. I’ve been maple sugaring since I was a kid.”

“I know you could have taught it, Gavin, but I didn’t want to give you too heavy of a workload. Plus, you’ll have a school visit at the same time. Between you and me, though, I’m starting to regret asking Beeson to speak. I thought his new book would be a draw for more guests, but he’s turning out to be a bit of a diva.”

Gavin barked a laugh. “I could have told you that.”

Before I could ask him what he meant by that comment, Judy, who was in charge of our ticket sales, walked over to where we were standing. “I just got a call from one of the schoolteachers. The buses left the elementary school. They should be here inside ten minutes.”

I nodded. It didn’t take more than ten minutes to drive anywhere in New Hartford.

“I’d better go check the sugarhouse before they arrive,” Gavin said, turning to go.

After he exited the visitor center, I asked Judy, “Have you seen Dr. Beeson? He left Benji and me in the maple grove. I expected to find him in here waiting for us. We were going to discuss the class he’s teaching tomorrow.”

Judy wrung her hands. Before she could answer, Benji approached us from the kitchen. “Alice is good to go,” she said.

“Great,” I said.

Benji looked from Judy to me and back again. “What’s going on?” She stared at Judy’s clasped hands and her eyes widened. Judy wasn’t the hand-wringing type.

Marshmallow Malice

Marshmallow Malice Verse and Vengeance

Verse and Vengeance Mums and Mayhem

Mums and Mayhem Toxic Toffee

Toxic Toffee Criminally Cocoa

Criminally Cocoa Assaulted Caramel

Assaulted Caramel Maid of Murder aihm-1

Maid of Murder aihm-1 Murders and Metaphors

Murders and Metaphors Matchmaking Can Be Murder

Matchmaking Can Be Murder Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery)

Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery) Andi Under Pressure

Andi Under Pressure Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3

Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3 A Plain Disappearance

A Plain Disappearance Andi Unstoppable

Andi Unstoppable The Final Vow

The Final Vow A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4)

A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4) The Final Tap

The Final Tap The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery

The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery Andi Unexpected

Andi Unexpected Lethal Licorice

Lethal Licorice Premeditated Peppermint

Premeditated Peppermint Death and Daisies

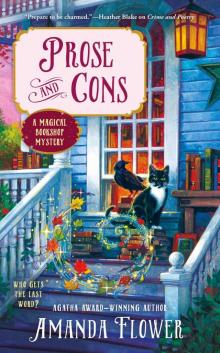

Death and Daisies Prose and Cons

Prose and Cons