- Home

- Amanda Flower

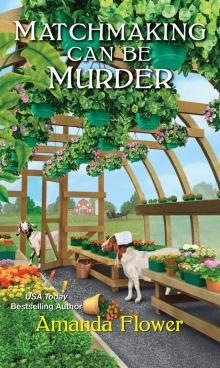

Matchmaking Can Be Murder Page 9

Matchmaking Can Be Murder Read online

Page 9

Deputy Aiden nodded and glanced at me again. His looks in my direction were beginning to make me nervous.

“Deputy?” Watterson asked, again shifting nervously from foot to foot.

“Yes?” Deputy Aiden asked.

“What do you want to do about the scene?”

“Secure it. I’ll be there in a little while. I’d like to speak to Mrs. Hochstetler alone.” Watterson and Deputy Little shared a look. “I would like you all to go outside. I won’t be long.”

The two men went out the door, scuttling by Ruth as they went. I couldn’t say that I blamed them for doing that. Her scowl at them was so fierce it would have scared a charging bull away. Ruth and I didn’t move a muscle.

Deputy Aiden’s face softened. “Ruth, Millie. I need you to leave too.”

“We are not leaving a young woman from our community alone with an Englisch man,” Ruth said. “That just isn’t right.”

“I think Deputy Aiden is trustworthy,” I said.

The deputy’s face turned bright red. “I am. I just need to ask Edith a few questions in private. If I can’t do that here, I will have to ask her to come to the station.”

“Well, I never,” Ruth began.

“Please,” Edith said, looking at us imploringly. “Please, just let him ask his questions, so that this nightmare can be over and the police will leave.”

“I don’t think—” Ruth began.

“All right, Edith,” I said, interrupting the bishop’s wife. “If that’s what you want, that’s what we will do.”

“It is,” she said with tears welling in her eyes.

There was so much I wanted to say to her, to ask her, but I couldn’t in present company. I couldn’t in any company.

I ushered Ruth out the door. When I went out, I left it cracked just a hair. A moment later, I heard the door click shut. So much for my plan to overhear their conversation. I stared at the closed door, wondering if I had done the right thing. I had no concern that Deputy Aiden would be unkind or treat my niece poorly, but I was afraid Edith would say something that would dig her even deeper into trouble.

Behind me, the bishop’s wife in was in the middle of a rant. “This has been most upsetting! Mark my words, this will bring trouble down on the district again. We can’t seem to steer clear of it. Bishop Yoder will be so upset, and the other Amish communities in the county will surely wag their tongues over our misfortunes,” Ruth said. “I don’t—ahhhh—!”

Her sentence broke out into a cry for help.

I spun around on the front porch to see Ruth Yoder being chased across my niece’s front yard by two Boer goats that I knew very well. The goats had silly grins on their faces and their ears flapped in the wind.

“Ahhh!” Ruth cried. “Millie Fisher, do something!”

I ran down the porch steps. “Phillip! Peter!”

The goats didn’t even bother to look over their shoulders at me as they chased Ruth in a zigzag pattern around the yard. They were having a ball of a time. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Edith’s children each holding a kitten or two while they tried to cover their mouths to stop laughing. Ginny held the little peach kitten that I had admired. The little animal was jostled with every giggle that escaped from the girl’s lips. He didn’t seem to mind it all that much. Maybe he thought he was being rocked to sleep in some strange way.

I felt my face crack at the reaction of the children, and I was just as tickled by Ruth’s predicament.

“Miiiillllleeeee!” Ruth cried.

The crime scene techs and some of Deputy Aiden’s officers came around the house from the greenhouse. It was officially a spectacle.

“Phillip! Peter!”

This time the goats had the gut sense to look at me. They could tell that I meant business from my tone, but they still didn’t come to me when I called them. The goats’ abrupt pause gave Ruth enough time to dash to her buggy. She grabbed the reins and untied them faster than I had ever seen a barrel racer do at the county fair. It was impressive.

“Millie Fisher, you need to do something about those goats!” She hopped into her buggy and kicked at the goats with her feet. Thankfully, they had the gut sense to stay clear of her shoes. “I’ll have a word with you later, Millie!” She flicked the buggy reins and her horse was spurred into action.

I knew that she would be going straight home to tell the bishop and everyone else who would listen what had happened at Edy’s Greenhouse.

I whistled again and the goats ran back to me like well-behaved Labs. I knew that I could have whistled for them when Ruth was running around the yard, but I’d conveniently forgotten at that time. Maybe I’d enjoyed the show just as much as the children. I would never be so bold as to tell Ruth that. I still had to quilt beside her in Double Stitch, and I knew in her mind that would be grounds for being kicked out of the group entirely.

The children ran over to the goats and me after Ruth left, and all the workers there for the investigation went back to their tasks.

Micah set the kittens he was holding in the grass and clutched his sides, he was laughing so hard. “Oh, oh, Aenti Millie. That was the funniest thing I ever saw. Did you know the bishop’s wife could run so fast?”

“Actually, I didn’t,” I said with a smile. “The last time I saw her run like that she was just a few years older than you when we were in school.”

Ginny covered her mouth, and then she held the peach-colored kitten out to me as a small child’s gift. I accepted the kitten and tucked him in close to my chest. Immediately, he began to purr.

“Aenti Millie,” Jacob said, “it looks to me like that kitten has picked you.”

Both of the goats’ ears perked up, and they inched toward me. I held the kitten out of their reach. Not that I thought the goats would hurt him on purpose, but they were clumsy and silly. That was how accidents happened.

As I snuggled the kitten close, I felt a match being made. There could be matches between people and creatures. That’s what I believed anyhow, and this little cat was my match. “I think you might be right. What should I name my new little companion?”

“Peaches!” Ginny cried.

I looked at the peach-colored kitten. “That’s just perfect, Ginny. Peaches it is.”

The kitten snuggled even closer, burying its downy head into my neck.

“I think he likes the name,” I said.

The front door of the house opened, and Deputy Aiden and Edith came out.

“Maam,” Micah said excitedly, “Aenti’s goats chased the bishop’s wife away!”

Deputy Aiden raised his eyebrows at me, so I explained. “The goats and Ruth have a strained relationship, mostly because they want to play with her and she wants nothing to do with them.”

“I see,” Aiden said.

Edith’s face was drawn. “Children, please take the kittens into the house and wait there for me.”

“But,” Micah whined, “we didn’t even get to speak to the policeman.”

“You have nothing to say to the policeman,” his mother replied firmly. “Now, do as I say and go into the house.”

Jacob gathered up four of the kittens, giving them to his brother to carry. “Come on, Micah. Maam said.”

Micah looked as if he wanted to argue some more, but one more stern look from his mother was all it took to keep his lips sealed.

Ginny reached up to me and I set Peaches in her arms. I was sad to see the little cat go, but I promised myself that I would take him home just as soon as he was weaned.

Deputy Aiden watched the children and kittens disappear into the house. “You have sweet children, Edith. I know this will be a difficult time for you, but please remember that I can only help you if you trust me. I want to keep you with your children just as much as you want to stay with them.”

“What are you saying?” I asked. “What’s going on?”

Deputy Aiden pressed his lips into a thin line, and Edith said nothing to make the deputy’s ambiguous words any cl

earer.

“I will see you at the station tomorrow, Edith,” Deputy Aiden said.

She nodded.

“Station?” I asked.

“We need to get a sample of her fingerprints. It will be easier to do that at the main office.” He rested his hand on his duty belt in a practiced way. “Now, I should go check on the crime scene one last time so that we can get out of your hair.” He nodded to Edith. “Please try to trust me. I have many friends who are Amish. I won’t do you wrong.”

She wouldn’t look him in the eye.

The deputy’s face fell just a little, and he walked away.

“What was that all about, asking you to trust him?”

She wouldn’t look at me either. “He’s a police officer. They want everyone in their community to trust them, don’t they?”

“I suppose . . .”

She turned to go back toward the house.

I followed, stopping her before she went inside. “Maybe you shouldn’t stay here alone. Why don’t you and the children come and stay with me? It might be a tight squeeze in my little house, but there is plenty of sleeping space in the living room. The children will enjoy it. It will be like a campout. We can make a game of it. They can bring the mother cat and kittens if they don’t want to leave them here alone. You know I love to have animals around.”

Edith frowned. “This is my home and my livelihood. I’m not going to leave. Whoever did this had a problem with Zeke. It has nothing to do with me. I see no reason for me to leave my home for his mistakes. The truth is, Aenti, I think you are the one who should leave.”

I stared at her. “You want me to leave.”

She wouldn’t meet my gaze. “Enoch will be back soon, and I think it’s best if you aren’t here when he arrives.”

I felt a stab of pain in my chest. I knew why she was saying this. Everyone, including myself, believed that I was the one who drove Enoch from the Amish way because I made a mistake that I couldn’t seem to make right.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Ten years ago when Enoch was in rumspringa, he was reckless. He smoked, got his driver’s license and a car. I heard rumors that he had gone to the wild parties that some of the young Amish threw. These were parties that no parent, Englisch or Amish, would want their child to be at. He was testing the absolute boundaries of his rumspringa, and I prayed for him every day.

By this time my Kip at been gone for ten years, and I’d spent the last few years living at Edy’s Greenhouse with my brother Ira and his twins. After my sister-in-law passed, they needed a woman to keep house for them while my brother ran his business. I was the widowed older sister. It made sense for me to give up my little home in the village and fulfill the family obligation. However, I had never had any children of my own, and even though I grew up in a family of many children, I didn’t know how to raise a child who was determined to be disobedient at every turn.

That’s the way Enoch behaved the moment he got out of school when he was fourteen and started rumspringa. He was defiant and sullen and made no attempt to help his father with the greenhouse. Edith was the one who was the perfect twin. She took interest in the greenhouse and learned all she could about plants. Enoch squandered away his time.

Enoch still lived at home when he started to dress like an Englischer. He cut his hair and bought expensive tennis shoes. I never knew where he got the money for those shoes. Instead of plants, he was interested in cars and motorcycles, and I found magazines about both in the barn, where he spent most of his time when he was home, which wasn’t often.

Ira would not do anything about the boy. He believed that Enoch was acting in such a way because he’d lost his mother when he was young. I felt sympathy for Enoch’s loss, but I didn’t believe that was his only reason for acting up. I did believe it was his excuse. I tried to speak to him many times and asked him to behave for his father’s sake, but my words fell on deaf ears. I was his aenti not his maam, so, as he told me many times, I really didn’t have any authority over him.

Then a motorcycle went missing. An expensive motorcycle was taken from an Englisch neighbor’s garage. The police came to the greenhouse to see if any of us knew about it. I was the only one home at the time. They said that the neighbor suspected Enoch had taken the motorcycle and they were looking for him. The neighbor told them that Enoch made no secret of how much he wanted that motorcycle. They only had a few questions to ask Enoch about it.

Despite everything that Enoch had done since beginning rumspringa years before, I told the police that I didn’t believe he would steal. It would go against his very nature as an Amish man.

Even so, they asked me where they could find my nephew, insisting they only wanted to speak to him about the motorcycle, and I told them. That was my worst mistake.

I never said he took it. Those words never came out of my mouth. But that small fact didn’t matter to the arresting deputy at the time, who was Marshall Jackson—Deputy Jackson, who was now Sheriff Jackson, a man who hated the Amish, and wanted to blame my culture for everything that went wrong in Holmes County.

When he came to the greenhouse asking after Enoch, I had been intimidated by his size and his hostile demeanor. And as soon as he learned Enoch’s whereabouts, he tracked him down. I don’t think he even spoke to Enoch before he arrested him and charged him with the crime. Enoch sat for weeks in jail, and there was nothing anyone from our district could do to free him. I even went to the sheriff’s department myself to explain that I didn’t think my nephew had done anything wrong. I was ignored at every turn.

After days of trying, I finally found the only person who would listen to me: Deputy Aiden. He believed me, and he promised he would do all he could to get Enoch out.

In the end, he did by continuing to follow leads until he found the missing motorcycle over fifty miles away. It had been stolen by an Englischer from another county.

It took some doing on Deputy Aiden’s part, but Enoch was eventually released from jail. Unfortunately, the damage was done. Enoch blamed me and the rest of the Amish community for his arrest, and he left the village.

After Enoch left, life at the greenhouse was fractured. My brother made it no secret that he partially blamed me for Enoch’s leaving. When I heard that my oldest sister was ill in Michigan and needed twenty-four-hour care, it only made sense to go to her. Edith was old enough at that point to help her father and to keep house for him and work in the greenhouse. She had recently married Moses Hochstetler, who would live at the greenhouse as well. I wasn’t needed or wanted any longer. I knew that I had to start over and as the saying goes, “Begin a journey by first deciding on a destination.” That’s what I did.

I was lucky in some ways that Edith never blamed me for her brother’s leaving as her father had. That would have truly crushed me. However, now she was telling me to leave the greenhouse before Enoch returned, and I had to wonder if she had held me responsible all these years. If that were true, I wasn’t sure I could recover from it. I was wondering if I had made a terrible mistake coming back to Ohio.

“Is that what you want me to do?” I asked.

“Ya,” she said. “It’s for the best, Aenti. I know that Enoch would like to see you eventually.”

“Has he said that?”

“Nee, not in so many words, but I don’t think now is a gut time with what has happened. And if you could ask members of the community to stay away too, that would be helpful.”

I frowned. “The community will want to gather around you during this difficult time. That is the Amish way.” I couldn’t understand that part of her request. I knew why she didn’t want me there, but why not the rest of the district? Whether someone dies, is hurt, or is just upset, we all come out to show that person compassion and love. Edith knew this. To ask district members to stay away could lead to a misunderstanding, and I wasn’t sure how her request would be received by the community. More assumptions would be made.

“Enoch is not ready to see them, and I would

prefer not to be overwhelmed by visitors. It took me months to convince Enoch to come stay with me. Too many people might drive him away.” She looked at me with tears in her eyes. “After what has happened with Zeke, I so much want my brother to stay and rejoin our family, rejoin our faith. We can’t rush it if we’re going to have any hope of success. I need him to come back. I’m not sure I can do this alone any longer.”

She had a point. Even with the best intentions, the community’s enthusiasm for his return might scare Enoch off. People would have many questions about where he had been and what he had been doing over the last ten years. I had those questions too. I’d never expected to see my nephew again and wanted to know how Enoch was. There would be questions too about why he didn’t come back when his father died. The community would be caring, but some, like Ruth Yoder, would want answers. I could see now why Edith would like to ease Enoch back into our culture.

“All right.” I nodded. “I will do as you ask on both counts.”

“Danki, Aenti. I know that you must have many questions for Enoch, but please try to hold them back.” Tears came to her eyes. “I have missed him so much, especially now that our parents are gone. I’m hoping he will work with me at the greenhouse.”

“Would you turn the greenhouse over to him?”

A strange look passed over her face. “I would have to do that if he rejoined the church, wouldn’t I? That’s the Amish way—the man in the family inherits the property. If I had married before Enoch returned, it wouldn’t have been an issue because the business would have gone to my husband. He would have missed his opportunity to reclaim the greenhouse.”

I wondered if she realized that she’d just given her brother a motive to murder Zeke. He was in the village when Zeke died. More specifically, he was at the greenhouse. That was opportunity.

Edith shook her head. “I don’t think ownership of the business will really be an issue. I doubt that Enoch will want the greenhouse or anything to do with our way of life. I have asked my brother so many times to come back into the fold of the church, but he has no interest in it.”

Marshmallow Malice

Marshmallow Malice Verse and Vengeance

Verse and Vengeance Mums and Mayhem

Mums and Mayhem Toxic Toffee

Toxic Toffee Criminally Cocoa

Criminally Cocoa Assaulted Caramel

Assaulted Caramel Maid of Murder aihm-1

Maid of Murder aihm-1 Murders and Metaphors

Murders and Metaphors Matchmaking Can Be Murder

Matchmaking Can Be Murder Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery)

Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery) Andi Under Pressure

Andi Under Pressure Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3

Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3 A Plain Disappearance

A Plain Disappearance Andi Unstoppable

Andi Unstoppable The Final Vow

The Final Vow A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4)

A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4) The Final Tap

The Final Tap The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery

The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery Andi Unexpected

Andi Unexpected Lethal Licorice

Lethal Licorice Premeditated Peppermint

Premeditated Peppermint Death and Daisies

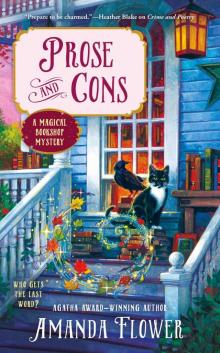

Death and Daisies Prose and Cons

Prose and Cons