- Home

- Amanda Flower

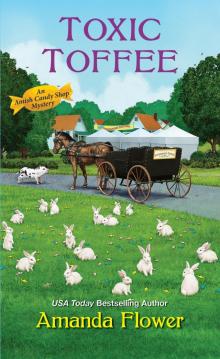

Toxic Toffee Page 9

Toxic Toffee Read online

Page 9

“I’d be happy to look.”

“Wonderful.” She dropped her gloves in the grass and scooped up Jethro. It wasn’t until that moment that she noticed what he had done. “Jethro, did you dig up all those flowers I just planted? You naughty, naughty pig,” she cooed, and then hoisted him on her shoulder.

Jethro smiled at me over her shoulder, and I rolled my eyes at him.

I followed the pair toward the church’s rear entrance.

“How did they get in?” I asked. “I thought the church invested in new locks.” I knew that because, unfortunately, this wasn’t the first time the church had been broken into through this very door.

Her face turned red. “Well, it seems the door was left unlocked.”

I raised my eyebrows. “Why?”

“Margot and her people have been using our fellowship hall to store things for Easter Days. We don’t mind at all. It seems when they left for the night before the break-in, they may have forgotten to lock up behind them.”

“How, then, do you know it was a break-in? Couldn’t it have been a member of Margot’s team who caused the mess?”

She unlocked the door and we walked inside. I followed through the short hallway into the church’s large kitchen. It may have been a mess yesterday morning, but now everything was perfectly clean. I knew that Juliet and the other church ladies must have been itching to get in the kitchen and disinfect the place after the intruder.

“Margot insists that it was spotless when she and the others on her committee left for the night. She said she was the last one to leave.”

I raised my eyebrows. “So, Margot forgot to lock the church?”

Juliet nodded. “Yes, and she feels awful about it.”

I frowned and made a mental note to speak to Margot again about the night she and the committee were in the church. Maybe there was something she would remember that could lead us to the intruder. As I looked around the clean kitchen, I knew there was very little I would be able to glean from the scene. There was nothing left to indicate that anything at all had happened in this room. The church ladies were thorough in their cleaning. “What was the person cooking in here?” I asked. “I can’t tell since everything has been put away. You told me yesterday that it was sticky like candy.”

“It was candy,” she said.

I turned to face her. “What kind of candy?” I asked, but deep in my heart I already knew.

“Toffee.”

* * *

I left Juliet and Jethro in the church’s kitchen shortly after that. I walked into the parking lot and to the edge of the graveyard at the perimeter of the church property to make a call.

Aiden picked up on the first ring. “Bailey, are you all right?”

“Why didn’t you tell me it was toffee?”

“Toffee? You mean the toffee that Stephen ate?”

“No, well . . . maybe.”

“No, well maybe what?” Aiden asked, sounding exasperated.

I knew he was busy. He didn’t have time to play guessing games with me, but I was so frustrated with him for keeping this important fact of the case from me. I took a breath. Aiden didn’t have to share anything about the case with me. He was the cop; I wasn’t. I needed to remind myself of that before I accused him of anything.

Much more calmly, I said, “You didn’t tell me that the candy that was made during the break-in at the church was toffee.”

He was silent for a moment and asked, “Where did you hear that?”

“Your mother told me.”

He grunted into the phone.

“Is that where the toffee was made that killed Stephen?”

“Yes,” he said finally. “We tested the samples I took from the church in the lab and it’s a match. I’m hoping to get back to the church today to take another look.”

“Did you tell the church ladies that? Because the place is spotless. They disinfected the entire kitchen. You aren’t going to find a fingerprint in that room.”

Aiden groaned. “I told Reverend Brook not to touch anything.”

“I doubt the reverend was the one who cleaned up the mess. You should have told your mother. She was the instigator with spray bottle and scrub brush.”

Aiden made a noise that was something between a groan and a squeak.

“You okay?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said after a beat. “Just frustrated. The sheriff is not going to be happy with me if he finds out my own mother tampered with a crime scene.”

“Oh.” I grimaced. I knew that Aiden wanted to avoid trouble with the sheriff at all costs. He was already on slippery ground with his boss. “I’m sorry, Aiden.”

“It’s not your fault. Don’t say sorry for something that you didn’t do.” He had said this to me countless times, and I was still guilty of it. I supposed I was used to taking responsibility for things that went wrong. It had been my job to do so as Jean Pierre’s first chocolatier in New York. If something went wrong for one of the big clients, I had to take the heat. It was just part of the job and a way to test whether I could eventually handle Jean Pierre’s position. Ironically, I knew that I could handle it but chose to give it up for the life I had in Harvest.

“I think,” I said, “we need to get together to solve this murder. I can talk to the Amish and you can gather evidence and talk to the non-Amish who may be involved.”

“No, Bailey,” was all he said.

“Did you know about the quilting circle?” I asked.

There was resignation in his voice. “What quilting circle?”

I went on to tell him what I had learned from my grandmother about Stephen’s late wife Carmela and her closest friends in the quilting circle. “You have to admit that I will have much more luck talking to them than you would.”

He sighed. “You’re right there. I can’t believe I’m about to say this.” There was a pause on the line. “Okay, Bailey, you have a deal. We will work on this together, but I want you to tell me your every move. You leave Swissmen Sweets, I want a text about it.”

I grumbled.

“No complaints. I want you to be safe.”

“All right,” I finally agreed. “I want to find Ruth Yoder and talk to her about the quilting circle, and I’m going out to Keims’ Christmas Tree Farm too.”

“Why are you going there?”

“Because Daniel Keim was the one who sent Eli to me. He must be close to the family or know someone who is closer who can tell us what Stephen did to get himself killed.”

“You still think that the death is tied to those notes?” he asked.

“And you don’t?” I challenged.

He sighed. “I didn’t say that. I don’t like the idea of you going out to the Keims’ alone.”

“Aiden, I go there all the time to pick up and drop off Emily. It won’t be a big surprise to any of them if I just happen to stop by.”

“I suppose not,” he said with resignation. “When are you heading out there?”

“Within the hour, I hope. I have to run back to Swissmen Sweets to make sure that my grandmother and Charlotte can spare me for a few hours. Luckily, we got all the candy done for Easter Days and most of the Easter special orders too. The only big project I have left is the toffee rabbit. I should have it done tonight, although it will be late.”

“You’ll be working late at the candy shop?”

“Most likely.”

“Then, I think you should stay there tonight. There’s no sense going home when you have to be up at the crack of dawn the next morning.”

“Aiden,” I started. “I’ll be fine. Besides, I have to go home tonight. I have Puff to take care of, remember? I’m going to stop on my way out to the Keims’ farm to make sure that Puff is okay.”

“Oh, I forgot about the rabbit,” Aiden said. “Just be careful. Text me when you leave the candy shop. I don’t care what time it is.”

“I think you are being more than a little paranoid.”

“Am I? A man is dead, B

ailey. He was poisoned by a candy made in a church. Whoever planned this did it in a calculated sort of way. That’s not the sort of person you want to mess with.”

“No, I suppose it’s not,” I said quietly, and ended the call.

Chapter 15

I hurried back to Swissmen Sweets, taking the long way around the square to avoid being spotted by Margot. I knew that she would track me down eventually, but I would rather it be later than sooner.

I pushed open the door to the shop and was happy to see a line at the counter. The shop was doing a brisk business as people stopped by to pick up their Easter orders for the end of the week and tourists stumbled in from Easter Days.

As aggravating and demanding as Margot could be with her many ideas to raise the profile of Harvest, no one could argue that her methods didn’t get results and tourists into the village.

I helped Charlotte and my grandmother for a half hour, until the line died down. Then I removed my apron. “I’m going to go to Keims’ Christmas Tree Farm to see what I can learn from Daniel about Eli.”

“Did you find Ruth Yoder at the square?” Maami asked.

I shook my head. “She was gone by the time I got there.”

My grandmother nodded thoughtfully. “You might have more luck finding her husband’s woodworking shop, Yoder Furnishings. It’s not too far from here. I’m sure you’ve passed it many times driving through the village.”

“Yoder Furnishings is the bishop’s store?” It wasn’t surprising that I didn’t know it belonged to the Yoders from my grandmother’s district. Yoder was the number one surname in Holmes County. It was like Smith, but as if all the Smiths decided to move to the same little corner of Ohio. It was hard to drive through the county without seeing the last name on half a dozen buildings. At least to me, it was impossible to see which Yoders were related to which.

“It is their store,” my grandmother said. “The bishop is too frail to make furniture there any longer. His boys took over the day-to-day work years ago, but I’m certain Ruth still keeps the books.”

“I’m sure she’s good at it,” I said. Ruth Yoder had a reputation as a stickler for details. She was just the kind of person who would make the perfect bookkeeper, especially since many Amish businesses still kept their books in actual ledgers.

It was taking some work, but I was pulling Swissmen Sweets away from that, and entering our accounts into computer software. It was a long process, and I hadn’t got much of it done before I had to leave for the filming in New York. It was yet another project I wanted to complete before I got called away to the city again by Gourmet Television.

“I think I’ll stop by the furniture shop after leaving the Keims.”

My grandmother nodded. “That does sound like a good idea. Daniel will tell you the truth about his friend, but don’t be gone too long.”

I raised an eyebrow.

“Margot stopped by while you were out and wanted to see the toffee bunny. I wouldn’t let her back into the kitchen. I know how you hate to have your creations critiqued before they are done.”

“Thanks, Maami,” I said, thinking that Margot must have come to the shop while I had been at the church.

My grandmother peered at me over her glasses. “Did you really promise her that it would be seven feet tall?”

I gaped at my grandmother. “No. I said six feet. No one said anything about seven!”

“Well, it seems she found out that the biggest toffee bunny ever made was six and a half feet tall, so she wants yours to be seven. I think she was really looking for eight though.”

“Of course she was,” I grumped. “That woman is going to be the death of me.”

“I’m sure you’re not the first one to say so,” my sweet Amish grandmother replied with a smile.

Shaking my head, I left the shop to head toward Keims’ Christmas Tree Farm.

It was on a remote road that was little more than loose gravel with overgrown grass on either side. There was no berm to speak of. Even though there were few street signs and even fewer landmarks, I knew the way there because I had visited the farm often in the Christmas season, and I had taken Emily home many times since she and Daniel had married.

Driving down the long street, I felt glad for Emily. I knew she had married Daniel very quickly after a whirlwind courtship, but she appeared to be happy, and after years of being ridiculed and mistreated by her older sister and brother, she was finally out from under their control. Thinking on that, I supposed Aiden was right. The Amish were similar to the English in that way—likely all people were—you had your good, your bad, your indifferent. While I did believe that the Amish had fewer of the societal flaws I had encountered in the big city because their faith instilled in them a strong sense of family and community, driving them to place God and family first, I think there was occasionally a downside to their focus. Such strong adherence to their ways meant that sometimes, if someone didn’t conform to the model dictated by their bishop or ordnung laws, that person was ostracized or berated. In Emily’s case, the girl’s brother and sister truly believed they were doing the right thing, that their harsh treatment of her was only showing her the error of her ways. But that kind of punishment smacked a little too close to mistreatment for my comfort. And what of poor Stephen, the gentle rabbit keeper? From the notes he’d received, it was clear someone deemed themselves judge of his actions, and that someone thought to punish him too—and they’d succeeded.

I shuddered and forced the thoughts away.

Emily’s family owned Esh Family Pretzel, which was right next door to Swissmen Sweets. I wished I had a better relationship with the shop owner, Esther, Emily’s older sister, but when I’d helped Emily get away from her repressive siblings, I’d ended any chance of making up with Esther or the girls’ older brother, Abel. It was all worth it to me because now I knew that Emily was living with a loving family.

The Keim family made most of their income around Christmastime, selling the beautiful Christmas trees they grew, but that wasn’t enough to last them the entire year, so they also sold cash crops to wholesalers and farmers’ markets. Emily said that this year the crop would be soybeans, alternating from corn last year. The Amish farmers alternated crops to keep the soil healthy. It was better for the land that way.

The soybean fields were freshly plowed. It was April, but an unusually warm April. The land could be tilled up and made ready, but it would be a few weeks before the seeds were in the ground. In Ohio there could be frost right into May, and seasoned farmers like the Keims would know better that to taunt Mother Nature by getting too far ahead of themselves. If the weather held, it promised to be a beautiful Easter at the end of the week. My prayer was that the mystery surrounding Stephen’s death would be solved by then, so the village could enjoy the holiday without his untimely death hanging like a cloud over our heads. I knew the Amish community, in particular, must be on edge with this sad turn of events.

I turned into the Keims’ long, gravel driveway, and the loose pebbles crunched under my compact car’s small tires. In the late afternoon, the farm was quiet. Just beyond the large white farmhouse and white barn, I could see the Christmas tree planting. It looked like the Keims had been expanding by planting new saplings on the edges of the more mature trees. I smiled. Tulips and daffodils bloomed in the front garden. I was glad the family was doing well. They had had a very difficult Christmas. I hoped that Easter would be a much brighter season for them.

I knocked on the front door. Inside, I heard the thunk, thunk, thunk of a cane hitting the hardwood floor. A few moments later, the front door opened and Grandma Leah’s face broke into a grin. Grandma Leah was well into her nineties and was the oldest woman in my grandmother’s Amish district if not the entire Amish community of Holmes County, but you wouldn’t know that. Except for her cane, which was a recent addition after she took a tumble in the barn over the winter, you would never be able to guess her advanced age. She held herself erect as if she was still on

a mission to prove that she didn’t need the cane to hold her up.

Thad was Daniel’s father and Grandma Leah’s grandson. Grandma Leah, Thad, Daniel, and Emily all lived in the big white farmhouse. It was certainly large enough for the multigenerational family. However, Emily told me that she and Daniel were toying with the idea of building their own little house, a daadihaus, on the farm to have some privacy. This surprised me. Privacy, at least privacy from other family members, wasn’t something the Amish typically valued. I thought it showed a generational shift from Thad’s generation to the next and certainly a giant leap from Grandma Leah’s time.

“My,” Grandma Leah said. “Aren’t you a sight for sore eyes? I heard that you were in the city making a television show. What on earth has brought Bailey King to my doorstep?” She leaned forward on her cane. “Is it trouble? It seems the only thing that brings you here when Emily is away is trouble.”

I grimaced, wondering if that were true and thinking it just might be. “I was in New York, but I’m back now for a little while at least.”

“Gut. I know Clara would want you home for Easter. It is a time that family needs to be together.” She thumped her cane on the floor for emphasis. “Are you here to see Emily? I sent her on an errand to Millersburg to pick up my medicine from the pharmacy. She went in the buggy, of course, so she won’t be back for a long while. I hope she wasn’t supposed to work at the candy shop today. She told me she didn’t have to.” She said all this without taking a single breath.

I smiled. “No, I’m actually here to see Daniel. Do you know where I might find him?”

She raised her eyebrows. “Now I know that you are here because of some kind of trouble.”

Before I could answer, she went on to say, “It’s Stephen Raber’s death, isn’t it? I should have known that was what it was the moment I heard your car come up the drive. You don’t think my Daniel had anything to do with it, do you?”

Marshmallow Malice

Marshmallow Malice Verse and Vengeance

Verse and Vengeance Mums and Mayhem

Mums and Mayhem Toxic Toffee

Toxic Toffee Criminally Cocoa

Criminally Cocoa Assaulted Caramel

Assaulted Caramel Maid of Murder aihm-1

Maid of Murder aihm-1 Murders and Metaphors

Murders and Metaphors Matchmaking Can Be Murder

Matchmaking Can Be Murder Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery)

Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery) Andi Under Pressure

Andi Under Pressure Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3

Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3 A Plain Disappearance

A Plain Disappearance Andi Unstoppable

Andi Unstoppable The Final Vow

The Final Vow A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4)

A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4) The Final Tap

The Final Tap The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery

The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery Andi Unexpected

Andi Unexpected Lethal Licorice

Lethal Licorice Premeditated Peppermint

Premeditated Peppermint Death and Daisies

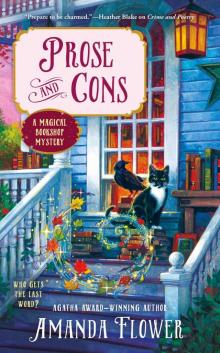

Death and Daisies Prose and Cons

Prose and Cons