- Home

- Amanda Flower

Matchmaking Can Be Murder Page 5

Matchmaking Can Be Murder Read online

Page 5

“I see,” I said, trying to keep a straight face, which had never been my strong suit when it came to children.

“Onkel Enoch would like them too. He said he misses Amish cooking.” He lowered his voice. “Onkel Enoch is an Englischer.”

My pulse quickened. “Have you seen him?”

“He’s been here for a few days.”

Days? Why hadn’t Edith told me? This might finally be my chance to set things right with my nephew.

“He’s not here now,” Jacob said. “He left this morning right after breakfast. He said he had business in the village.”

I frowned. “Business on a Sunday in Harvest? Almost every place is closed.”

“Maam was disappointed because she wanted him to come to church with us,” Micah said. “But we have been waiting here for so long, I don’t think any of us are going to church now.”

I suspected that he was right.

“Aenti Millie,” Jacob said. “Is everything all right with Maam?” He looked as if he might cry. I knew that the stress of being a man at such a tender age weighed on him. I wished that wasn’t what was expected of him in our district, but there was no help for it until his mother chose to remarry, if that day ever came. I knew that she wouldn’t be marrying Zeke.

“Why do you ask that, my boy?” I asked.

He glanced at his younger brother and sister.

“Micah, why don’t you and Ginny check inside my buggy? There might be a plate of cookies under the bench seat.” It never hurt to have a spare plate of cookies at the ready for any and all situations, but it came in especially handy when one was trying to distract children.

Micah pumped his fist in the air. “Yay!” He then took off in the direction of the buggy.

Ginny clapped her hands, seemingly recovered from her worries over the kittens, and followed Micah as fast as her much shorter legs could carry her. Jacob watched them go with a tired expression on his face. I wished I could take all the strain and worry off of his thin frame.

“What is wrong with your maam?” I asked.

He looked down at the tops of his plain black sneakers. “She was crying last night, and it was different from when she cried before.”

“Cried before?” I asked.

“Like the times that she cried over Daed dying. Those tears were different from these tears. The tears that she cried last night were . . .” He trailed off.

“What were they?” I asked, my voice barely louder than a whisper.

“They were angry.” He looked up at me with bright green eyes that brimmed with tears of his own. Tears that he did not let fall because he was conditioned to be brave. “She was angry, and I didn’t know what to do about it.”

There was nothing more I could ask him because then the younger children ran back to us with the plate of cookies in their hands and chocolate smeared on their cheeks. It seemed to me that they had not waited before sampling my famous chocolate chip cookies. I couldn’t say that I blamed them. I did make the very best chocolate chip cookies that I had ever had. Perhaps that’s boastful, which is a shameful trait, but that doesn’t make it any less true.

“Where’s your maam now?” I asked.

“In the greenhouse,” Jacob said. “She told us to play in the front yard. She was upset. She said she didn’t want us back there until she knew what to do.”

“What to do about what?” I asked.

He shrugged. “I don’t know.”

I frowned. That didn’t sound like my Edith at all. She always wanted her children around her. Some in our district believed she clung to the children too much after the death of her husband and felt that she was smothering them. I knew I had been away for many years, but I never saw that behavior in my sweet niece in the months since I had been home.

I had a sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach that something was very wrong with Edith. She must be taking her broken engagement with Zeke much harder than I thought she would. The day before, when she’d told me that she planned to break it off, she sounded so sure and calm about her decision. Her voice let me know that she wasn’t looking forward to talking to Zeke, but there was nothing to indicate that she was distraught. However, bravery before an act didn’t mean there wouldn’t be emotion and repercussions afterward. Perhaps she was just experiencing the emotional letdown and relief from what she had done.

“You children stay here like your maam asked you to do, and I will go check on her.”

Jacob grabbed my hand. “Aenti Millie, tell Maam I want to give her a hug. She says our hugs help anytime that she’s sad.” He stared up at me with such earnestness in his eyes that my heart broke a little. What was Jacob sensing for him to be this concerned? He was a serious child but rarely was so fearful. In fact, I couldn’t remember a time I thought he was afraid.

I headed to the greenhouse. Just outside the building, Phillip and Peter bleated from a small pen. I walked over to them. “I heard the two of you were troublemakers and got penned up because of it. I’ll take you home just as quick as I can. Let me check on Edith first.”

Ruth would chastise me for talking to the goats as if they could understand what I was saying. It was a gut thing she wasn’t at my house most of the time. Living alone, I’d had some very long conversations with the goats. I knew they listened even if they didn’t know what I was telling them.

I patted both of their heads and walked to the greenhouse’s main door. It was unlocked, which was what I expected. When I stepped into the greenhouse, the early morning light came through the corrugated plastic over my head. It was spring, and the building was bursting with flowers and color. Everywhere I looked there was another beautiful blossom. I wanted to stop and inhale the sweet fragrance of every last one of them. I loved flowers almost as much as Edith did, but I wasn’t nearly as talented in caring for them as she was. She got her green thumb from her father, Ira, and he would be proud to see her keeping the greenhouse going without Enoch’s help. Sometimes I wondered if Enoch had no interest in the greenhouse because it was named after his sister and not him or not both of them. Ira only had the two children. It was as if when he’d named the greenhouse after his daughter, he’d declared his favorite between the twins. There was jealousy in a family when it was so clear who the favored child was.

I went through the cooler section of the greenhouse to the hothouse plants. There was no sign of Edith in either place. The last room she could be in would be the small area where desert plants were kept. Edith called this the “cactus room” because of the sheer number of spiny and thorny succulents inside it. These sorts of plants didn’t do well outdoors in Ohio’s humid summers and died in the winters from the freezing cold, but they were popular houseplants with the Englischers, which was why Edith kept them.

Finally, I reached the cactus room. There was a prickly pear cactus on the table with its pot turned on the side. Soil spilled out onto the tabletop. Edith stood beside the fallen cactus and was staring at something on the floor on the other side of the workbench. She didn’t hear my footsteps as I entered the room.

“Edith?” I asked in a low voice. She was concentrating so hard on whatever she was looking at, it felt wrong to interrupt her.

She didn’t so much as twitch when I spoke. Instead she stared at her feet.

“Edith?” I repeated.

Again, there was no answer. I took another step forward, peeking around the side of the potting table, and stopped in my tracks. I couldn’t be seeing what I was seeing. It was a foot attached to a leg that was attached to the body of Zeke Miller, who was lying on his stomach on the concrete floor. His left cheek was pressed on the floor so that I could see his face. Blood pooled on the concrete around his head. Thankfully his eyes were closed. I would remember the scene for the rest of my days.

“Edith?” I asked, my voice sharp now.

She finally looked at me. “Oh, Aenti Millie. What have I done?”

CHAPTER SEVEN

I stared at her and blinked my ey

es several times. What had she done?

This couldn’t be possible. There was no way that this nightmare unfolding before me could be true. “Edith?” I whispered. My voice sounded strange and foreign to my own ears. I didn’t even recognize it as my own. “Did you . . . ?” I couldn’t finish the question. My mouth ran completely dry.

Tears ran down her face. “I told him I wouldn’t marry him, and look what he has gone and done to himself. It is my fault!”

I blinked as the fog in front of my eyes began to clear. “You think he killed himself because you broke off the engagement?”

“Ya, why else would he be dead? He was a healthy young man.” She wrapped her arms around her waist and bent slightly forward, as if holding herself upright was far too much of a burden.

“Step back. You look as if you will be ill.” I touched her arm.

“I feel like I will be ill. I feel like my heart has been punctured through. Oh, Aenti, how will I ever go on, knowing what I made him do?”

I was relieved when she shuffled backward a few steps and allowed me to take a closer look at the body. Despite my distaste for the scene, I examined Zeke. “My girl, a man cannot bash the back of his own head in like this. It seems that there has been some sort of accident. Maybe he fell and hit his head in just the right spot. It’s terrible but not your fault. He didn’t kill himself.” I looked at the potting table for any sign as to where Zeke’s head might have come into contact with the wood. I saw nothing. Nor could the overturned cactus have made the wound on the back of his head. “He must have hit his head on something. It’s the only explanation.” I searched the room for something else he might have knocked his head on.

While I did that, Edith picked up a large decorative stone that was encrusted with blood and hair. “Like this?”

“Put that down,” I shouted at her.

She let it fall to the ground from her hand, and it bounced off the concrete and rolled under the potting table.

“What have I done wrong?” she moaned. “Should I get it?”

I didn’t want to tell her that the biggest mistake she’d made was picking up the stone that had killed Zeke. The police would find traces of her on it now. I knew this from the many times I’d been in the hospital with my ailing sister. It seemed to me that the televisions in the waiting rooms in those places were set to crime shows or news. Both I found depressing, and even though I did my best not to watch them and concentrate on my quilting while I waited, it was impossible not to hear them. “Nee, leave it there for the police.”

“The police? Aenti, you think we should call the police and not the bishop?”

“We should call both.” I winced at the very thought of what Ruth Yoder would say about this. I hoped that as my friend and a fellow member of Double Stitch, she would take mercy on my niece and not spread the rumors that were sure to fly in all directions, not just in Holmes County, but across the country throughout the Amish community. “There is no other choice. This is beyond what the district can handle. We will call the bishop, of course, but the police must be consulted as well.”

She began to shiver. “Oh, Aenti, it grows worse and worse.”

I removed the shawl from my shoulders and wrapped it around her. “My child, you have seen too much of this. Call the police and the bishop and then go into the house. Take the children with you. The bishop is home as church is at his house today. Someone will answer his shed phone. They will know that it would only ring on the Lord’s Day in the case of a dire emergency, which is exactly where we find ourselves this morning. I will stay here with . . .” I trailed off.

“You shouldn’t stay here with him,” she said. “That is something I should do since I am responsible.”

I placed my hands on either side of her face. “Look at me, child. Do not, do not say that when the police arrive. Answer their questions openly and honestly, but do not interject what you think might have happened. You may cause yourself and your family much grief if you do.”

She stared at me with confusion etched on her lovely face, and then the confusion cleared. “I won’t say anything more than what I know for sure.”

I patted her cheek. “That’s a good girl. Now, hurry and make those calls on the phone in the greenhouse office. When you have done that, I would like you to gather up the children and take them into the house. It is best if they see as little of the police as possible.”

Edith’s determination wavered. “I don’t want them to see any of this.”

I glanced down at Zeke. “Neither do I, but we might not be able to shelter them completely from what has happened. Gott will show you the way to tell them what has occurred when the time is right. Look to Him for guidance.”

Edith left the cactus room to make the call. I was grateful that she had a phone in the greenhouse, a luxury that she was allowed in our district because it was her place of business. The closest phone to my home was the shed phone that I shared with Raellen’s family. It was a half mile from my house on their sheep farm.

When Edith was gone, I took a tentative step forward and peered at Zeke’s face. He lay on his stomach and his left cheek was pressed into the cold concrete floor. His chin was clean shaven, of course, because he was never married, and he would never marry now. He would never marry Edith or anyone else.

I crouched beside the table and looked at the rock that Edith had dropped to the floor. I could see it just under the potting table. It was about the size of a large man’s fist. Edith had a number of decorative stones in various sizes for sale in the greenhouse. Her uncle, my brother, who owned a quarry a few miles away, had a hobby of polishing and etching stones to be sold. He was quite a talented sculptor and the Englischers seemed to like to buy them for their gardens. Not all stones had Bible verses on them, but this one did. I could just make out the words etched into the stone: “IF WE CONFESS OUR SINS, HE IS FAITHFUL AND JUST AND WILL FORGIVE US OUR SINS AND PURIFY US FROM ALL UNRIGHTEOUSNESS.”

Had Zeke died because of some sin? And who had killed him? Because now that I had seen the stone, I was certain that the man had been murdered.

I pressed my lips together, knowing this was the stone that had killed him. There was blood encrusted in one of the Bible verses. For the briefest moment, I wanted to hide the rock because I knew that Edith had touched it. Because she’d made this mistake, the police might come to the wrong conclusion. They might believe that she was capable of this terrible act, and I knew she wasn’t.

It would not be the first time a member of the family had been blamed for a crime that he or she didn’t commit. The first time had been my fault and had driven Edith’s brother, Enoch, away. I wasn’t going to let that happen to his sister.

I squatted next to the table. My knees cracked as I moved. The agility that I’d had in youth was no longer there, and I couldn’t be in this position for long without my body protesting loudly. I ignored the protests. I wanted to get a better look at the rock. I lifted my skirt so that it wouldn’t touch the floor. I was only inches away from the bottom of Zeke’s boots. Had Edith dropped it by his head, I might not have had the strength for a closer look. Being near his boot wasn’t nearly as unnerving as that would have been.

I saw the stone, but there was something else there. Something small and metallic. It was likely a gardening tool of some sort; we were in a greenhouse after all. The piece of metal was closer to the other side of the table. That was just fine with me. When I got up, it took a moment for my spine to align again. Perhaps I needed to start stretching in the morning right after my coffee. Not that I had known when I awoke that morning that I would be crouching by a potting table and putting my old muscles and bones to the test.

After moving to the other side of the table, I crouched again. This time I was relieved that my knees didn’t crack. The item under the table was a wrench about five inches long. There was black grease on the head of it. There could be many reasons why a tool such as this was on the floor of the cactus room of the greenhouse,

but the black grease seemed out of place. I couldn’t help but think the presence of the wrench had something to do with the dead man on the other side of the table.

There was a scraping sound behind me in the second room. I jumped to my feet and spun around. “Edith? I told you not to come back. You should be with the children.”

There was no response and a chill ran the entire length of my spine. “Who is there?” I cried.

There was no answer, and that’s when I knew that it couldn’t have been Edith. She would have answered me. She knew the state I was in and wouldn’t want me to worry, and worry I did. I wasn’t alone in the greenhouse with Zeke Miller’s body.

“Hello!” I inched to the door of the cactus room, which opened into the main showroom of the greenhouse where the rows and rows of annuals stood on tables as long as my house from end to end. “You need to show yourself. Who’s there?”

There was crash as a pot fell to the floor. The crash spurred me ahead and quenched my fear. As I reached the middle of the room, the back door of the greenhouse banged closed so hard that I thought it would crack the glass.

I slipped on wet concrete as I ran to the door but was able to regain my footing by grabbing onto a nearby table corner. My stumble took just long enough for the culprit to slip away.

I righted myself and threw the back door open in time to see a dark figure dash across the pasture and disappear over the hill.

Out of nowhere Phillip and Peter raced across the open pasture toward the man. The man yelped and the goats chased him. Clearly, they thought the man was playing some kind of game with them.

“Phillip! Peter!” I cried.

The goats ignored me and kept running after the man. With a shock, I realized he wore Amish clothing.

CHAPTER EIGHT

If I had only been younger or quicker on my feet, I could have caught the man running away from the greenhouse, but it would be of no use for me to go dashing over the pasture and down the hill in search of the intruder. I was more likely to turn an ankle than catch the intruder or whoever he was, possibly even the man who’d killed Zeke.

Marshmallow Malice

Marshmallow Malice Verse and Vengeance

Verse and Vengeance Mums and Mayhem

Mums and Mayhem Toxic Toffee

Toxic Toffee Criminally Cocoa

Criminally Cocoa Assaulted Caramel

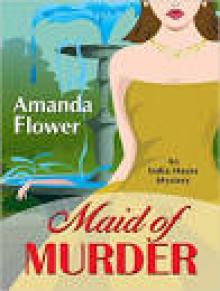

Assaulted Caramel Maid of Murder aihm-1

Maid of Murder aihm-1 Murders and Metaphors

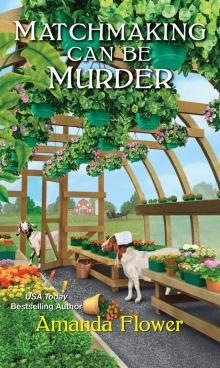

Murders and Metaphors Matchmaking Can Be Murder

Matchmaking Can Be Murder Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery)

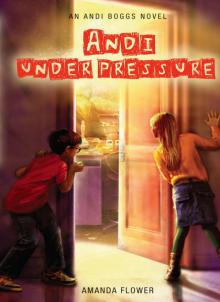

Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery) Andi Under Pressure

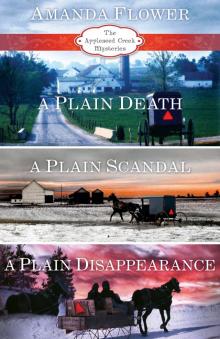

Andi Under Pressure Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3

Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3 A Plain Disappearance

A Plain Disappearance Andi Unstoppable

Andi Unstoppable The Final Vow

The Final Vow A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4)

A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4) The Final Tap

The Final Tap The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery

The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery Andi Unexpected

Andi Unexpected Lethal Licorice

Lethal Licorice Premeditated Peppermint

Premeditated Peppermint Death and Daisies

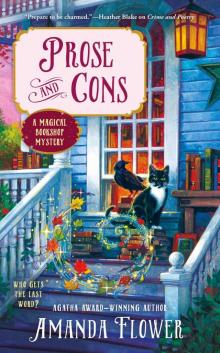

Death and Daisies Prose and Cons

Prose and Cons