- Home

- Amanda Flower

Verse and Vengeance Page 16

Verse and Vengeance Read online

Page 16

I almost mentioned her brother but stopped myself at the last second. Instead I said, “Sure, it sounds like Jo, but it could have been someone else. She’s not the only college student with an eyebrow ring.”

“Violet, there aren’t many people who are Jo’s stature who would be around the bikes the night before the race.”

“Well then, if she was there, she would have been there for her job. She has been working for Bobby.”

“I know, and maybe you’re right and it will be easy for her to explain, but nothing changes the fact that I need to talk to her. If she’s hiding, she’s not helping her case.”

“Maybe she doesn’t know you’re looking for her,” I argued.

“Violet, the entire village knows I’m looking for her.”

He had a point there.

He rubbed his cheek. “It’s been a long day, a long few days, and we’re both tired. Let’s talk about this again in the morning.”

I bit the inside of my lip. He was exhausted and so was I. No matter what my grandmother thought, now was not a good time to tell him that he was standing in the middle of a mystical bookshop with flying books. He needed his wits about him to fully absorb that.

Just as I made this decision, a book fell at Rainwater’s feet. The sound of the book hitting the old worn plank wood floor was like a gong going off.

Faulkner squawked. “Quiet. I need quiet,” he said. “I’m sleeping!”

“You’re not sleeping if you are talking,” I said to the bird. I knew I was making a lame attempt to distract Rainwater from the book. I made a move to pick it up, but the police chief was fast. He was closer to the book, after all. Even before he said a word, I knew what the title would be.

He picked up the book and stared at the cover. He flipped through the pages. “Something is going on here.”

My mouth felt dry. Part of me just wanted to tell him, but I couldn’t get the words out. They were stuck in my throat.

“I have no idea what’s going on,” Rainwater said slowly. “But I know Whitman’s involved.” He glanced at the tree and looked around the shop. “I know all of this is involved.”

I still didn’t say anything.

Quietly, Rainwater placed the book on the nearest bookshelf and picked up Redding’s guitar case. At the door he said, “Someday, I want you to trust me enough to tell me whatever it is you’re holding back.”

And then he was gone.

Chapter Twenty-Eight

The next morning, the shop was quiet, and I felt at a loss. I was used to going a million miles a minute, rushing from class to teach to the library to study to Charming Books to help Grandma Daisy at the shop. Now I had only one of those to do, and it felt off-putting.

I should enjoy the quiet. Charming Books would be overrun soon enough with summer tourists and special seasonal events. I should bask in the fact that there was nowhere I had to be, but I wasn’t very good at sitting still. I never had been. Since I was a child, I had been moving toward the next achievement, the next goal. A psychologist had told me once that it was because my mother was sick for much of my young life and died when I was just thirteen. Achievements and goals were something I could control, when all I wanted to control was my mother’s health. Maybe there was something to that.

The shop might be quiet, but I still had goals I wanted to achieve. The first of those was finding Jo. As I walked down the spiral staircase from my apartment to the main floor of Charming Books, I glanced at my phone. Over the last two days I had texted Jo a dozen times, but there wasn’t one return text. But as long as she had her phone with her, I knew the texts were getting through. According to my texting app, they had each been delivered and read.

At the cash register, I texted her again. IF YOU NEED HELP, LET ME KNOW. I’M YOUR TEACHER—AND YOUR FRIEND—FIRST. I WILL HELP YOU.

I waited for a reply. There was nothing. I started to put the phone back in my pocket when it pinged, telling me a new message was there. It was from Jo. A tiny heart emoji. I still didn’t know what she was doing or where she was, but seeing that tiny little heart gave me hope that she was okay. Part of me wanted to text back and ask where she was, but I stopped myself. Maybe I needed to give Jo time to come to me, and I realized I needed time to read Leaves of Grass.

Emerson jumped on the sales counter, his thin black tail whipping back and forth. Beside the cash register, books of Whitman’s poems were stacked seven high. I glanced at the tree. “Subtle.”

The page of the book at the top of the pile began to flutter, and then it fell open. Even though I had seen the essence work dozens of times, it still surprised me. Emerson, who was still on the counter next to the books, arched his back and hissed.

I ran my hand along his back and smoothed down his coat. Faulkner flew down from his perch in the tree and landed on a bookcase just a foot away from us.

I looked at the two of them. “I guess we’re all curious about what Whitman and the shop want to tell us.” With tentative hands, I picked up the book and carried it to one of the sofas in front of the fireplace. I perched on the coffee table and read “To Think of Time” again.

Frowning, I read on.

Not a day passes—not a minute or second, without an accouchement!

Not a day passes—not a minute or second, without a corpse!

The shop was reminding me that death was unavoidable. This I already knew. Perhaps, given my experiences, it was something I knew better than most people my age. However, what did this passage have to do with Redding’s death? I reexamined the line. Accouchement was an old-fashioned word for birth. Birth and death happened every day. Did Redding’s death relate somehow to a birth? I couldn’t think of any recent births in the village, but that didn’t mean I didn’t know about any. I would have to ask my grandmother. I thought the village made an announcement when a new villager was born. There were so few who lived in the village full-time that any babies were worth noting.

I couldn’t see how that line applied at all. I went back to the previous stanza. The line that struck me the most was:

Is to-day nothing? is the beginningless past nothing?

If the future is nothing, they are just as surely nothing.

It seemed to me that Whitman was asking the big questions that no one, not him nor anyone since, could give a clear answer to. I laid the book on my lap and waited. There had to be something else the shop’s essence wanted me to read. This couldn’t be all of it. This couldn’t be the end of the clues, because I wasn’t any closer to understanding what the shop wanted me to know.

But the pages didn’t move again.

I frowned and opened the book to a different page and read. Perhaps if I read the poems on my own, everything would be made clear. It was worth a shot.

Throughout the morning, a few customers came into the shop. All of them left with a book or two. The shop’s essence always knew what someone wanted or needed to read. I only wished it was clear about what it wanted me to understand from Leaves of Grass.

After the last customer left the shop clutching a cookbook to her chest, I went back to the couches and sat cross-legged in the one closest to the cool fireplace.

When the book didn’t open on its own, I opened it to arguably Whitman’s most famous poem in the book, “Song of Myself.”

A hand tapped me on the shoulder.

“Ahh!” I scream and threw my arm out. It connected with something soft. I blinked to see Richard standing in the middle of the shop.

“What are you doing?” I cried.

“You said you needed me to work this afternoon.” He rubbed his stomach.

“I’m so sorry. Did I hit you? Are you all right?” I jumped off the couch and let the volume of Whitman fall to floor. I scooped it up.

“That was the book the private investigator bought when he was here.”

“I know. It made me …” I paused. I tried to put into words my intentions without giving away too much. “Knowing that he read it … made me wan

t to reread it.”

He rubbed his goatee. “I was surprised that he chose Whitman. Of course, Whitman was the poet credited with creating American poetry. On the surface, his writing is deceitfully simple. It’s when you dig deeper, the challenge appears.”

I arched my brow. “Richard, you teach Shakespeare.”

He laughed. “Shakespeare in my opinion is a little more accessible than Whitman.”

I groaned. If Richard, who had spent the last forty-some years immersed in literature, had trouble understanding Whitman, I was doomed.

“I would think that you would have a better handle on the poet, since he’s a contemporary of Ralph Waldo Emerson.”

“I wish I could say that was true.” I read him the last poem that the shop had revealed to me, the poem about birth and death. “What’s you interpretation of that text?”

He paced back and forth in front of the fireplace, just like he did in the classroom in the middle of a discussion. Richard was a very good teacher and cared very much about connecting the great writers to the students in his class. “Of course it depends on what form of literary criticism you apply. With my students, I like to apply readers’ responses to start. It shows them that literature is something to feel and to be experienced. I would ask you, then, what this means to you, Violet?”

I looked down at the passage again, feeling a little irritated that he wouldn’t just give me the answer, but that wasn’t Richard’s way. I almost didn’t answer. “It’s about life and death. Mortality and immortality.”

“Is he telling the reader what to believe?”

I shook my head. “No. I wonder if he’s talking about another death.”

“What death?” Richard asked.

I didn’t answer and simply stared at the pages in front of me. Was the shop telling me that Redding and Bryant Cloud’s deaths were connected? Did I just want them to be?

“I have to go. Is there anything that you need?”

He blinked at me. “But I thought you wanted to discuss this piece of literature.”

“Maybe another time, Richard. I promise.” I headed to the door.

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Even on a slow weekday in the village, Le Crepe Jolie was busy between the lunch and dinner crowds. I didn’t think I had ever been to the café when there wasn’t another customer there. It was the most popular restaurant in the village and typically was included in the list of top places to eat for the region.

Lacey smiled at me when I walked in the door. “Here for a late lunch, Violet?”

“Maybe in a bit. Is Danielle here?”

Lacey’s eyes went wide. “Is something wrong?”

There must have been something in my tone to trigger her concern.

I smiled. “Nothing is wrong.”

She didn’t look convinced. “She told us about her ex-husband. It’s just horrible, and poor little Aster. I have no idea how she is going to tell her.”

“She hasn’t told her daughter yet?”

Lacey shook her head. “No, and I can’t say that I blame her.”

I didn’t either.

“Right now, she’s on her break. Usually if the weather is nice, she goes to the Riverwalk. You can look for her there,” Lacey said, not looking any less worried than she had when I first walked in the café.

I smiled my thanks. “Okay, I’ll go look for her, then.”

“Would you like a baguette before you go?” she asked.

I would, but I didn’t have time to waste if the poem was telling me there was a connection between Redding and Bryant. I had to find out what that connection might be. I left the café and walked across River Road to the Riverwalk.

Danielle was on a bench with her back to me, watching the rushing river. Her long black hair hung over one shoulder.

“Danielle?”

She turned, and there were tears in her eyes. Unlike her brother’s, Danielle’s eyes were a warm chocolate brown. “I have been wondering when you would come talk to me. I thought you might not because of my brother.”

I smiled. “I don’t want to upset David, but I need to know. One of my students from the college is in a lot of trouble. I have to help her.”

She smiled. “I know you’re a good teacher, Violet. I have overheard students studying in the café say how much they like you. They said you’re hard but you make class fun.”

“That’s one of the best compliments any teacher can have.”

“The student you’re talking about is Jo Fitzgerald, right?”

I nodded.

“I know Jo,” she said. “She’s a good kid, just a little confused, and …” She trailed off.

“And what?”

She shook her head, and I decided to let it drop for the moment. It seemed to me that several people in the village knew something about Jo that I was missing.

“Can you tell me about Redding?”

She turned away from me and stared out at the churning river. “I guess it’s better to start with Bryant. He was the most handsome man on the reservation, and he picked me. Maybe I was flattered at the beginning. Bryant and I got married very young. David told me that I shouldn’t marry so young, but I didn’t listen. I felt like I had been preparing to marry Bryant my whole life. We met as children, fell in love as teenagers, and it made sense to me that we would marry at the end of high school.” She looked at her hands. “But it was never easy. Bryant was angry a lot of the time. To others he was kind and charming, but with me at home, he could be harsh. Nothing I did was right, and if I really made a mistake, he would hit me.”

I squeezed her hand. “There is no mistake that you could ever make that warrants that. Ever.”

She squeezed my hand back before she pulled hers away. “Then I got pregnant. I was so excited, but scared too. I didn’t know what would happen when I had a baby. Bryant was so sweet to me while I was pregnant. He doted on me. He didn’t hit me once. I thought that he had realized his mistakes and was cured. It wasn’t long after the baby was born that I learned I was wrong, and he was back to the way he was before, maybe even worse. But he loved that baby and only looked on her with love. When the baby cried and woke him up, it was never her fault, only mine, and I was happy to take the blame for that. I loved her like I’ve never loved anyone else. I didn’t know what true love was until Aster was born. She loved me back. I knew it.

“Things were fine for a while. Hard, but I found ways to not give him reasons to be upset, but as Aster grew older, that became more difficult. I saw that he was beginning to give her the angry looks that he first gave me. He started to speak to her harshly, and she would shrink away from him. I knew it wouldn’t be long before he would hit her too. I left for Aster. He never hit her,” she said quickly. “Only me.”

I felt a lump in my throat. Those two words, only me, held so much weight.

“David knew none of this. He never liked Bryant, but he didn’t know what he was really like. When I decided to leave, I was too scared to tell my brother. I was afraid he would be disappointed with me for staying so long. To me, that was almost harder to take than all the blows Bryant had given me over the years.”

I cringed as she said this. I knew Rainwater would have dropped everything and run to his sister’s defense. He would have dropped anything and run to anyone’s defense in that situation. That was just the sort of man he was.

“So instead I ran away to New York City. I thought Aster and I could hide there. There were so many people, and there is a large Native American population there that I thought could help us get started. They did. I found a waitress job and a tiny studio apartment for us. My new friends watched Aster while I was at work. I was happy and I was free until Joel Redding showed up.”

“Bryant had hired him to find you,” I said.

She nodded. “‘You weren’t that hard to find.’ That was the first thing he said to me, and I knew Bryant had sent him. I knew he would tell Bryant where I was, so I called David.

“David

and Bryant showed up at the same time. It was a bad scene. The police arrested Bryant. David, for the next year, helped me navigate everything that I needed to do to get a divorce and full custody for Aster. It was awful.” She looked at me with tears in her eyes. “Never once did David blame me for what happened. Never once did he complain he was being saddled with my daughter and me.”

“He loves you both. He’s happy that you’re in the village. He wants you to live with him.”

She wiped at her eyes. “I know that, but I want to be out on my own too, and David needs his own life. Now that he has you, I know things will change.”

I wanted to ask her what she meant by that, but stopped myself. This conversation was for Danielle and what she needed to say, not about what he might have said to his sister about our relationship. “Tell me about when you saw Redding here in the village.”

“He came into the café. I was carrying a tray of food to one of the tables. I was so shocked to see him that I dropped the tray, which was the worst thing I could have done. He saw me, and I know he recognized me. I cleaned up the mess the best I could. Lacey helped. She’s so kind. Both she and Adrien are. I couldn’t ask for better bosses.” She looked out to the river again. “By the time we cleaned up the mess, Redding was gone.”

“Did you tell your brother?”

She shook her head. “Maybe I should have, but I wasn’t thinking straight. He had never met Redding. When he came to New York City to get Aster and me, I didn’t tell him everything that happened. I couldn’t bring myself to do it. As time went on, there didn’t seem much point to telling him everything. Aster and I were in Cascade Springs; I started to work at the café. We were happy. I didn’t feel the need to remember hard times.”

I could understand that, but I wondered how much damage Danielle had done to herself by not talking about it. I wished she and I had been better friends and she had felt comfortable telling me about her past. Or that she had tried to talk to Lacey. Lacey had her own traumatic history. The two of them could have healed together, but that was an opportunity lost now.

“Seeing Redding here in the village made me ill. This was the place where I rebuilt my life, and he had no business being here.”

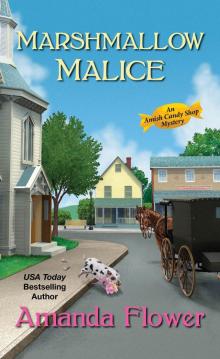

Marshmallow Malice

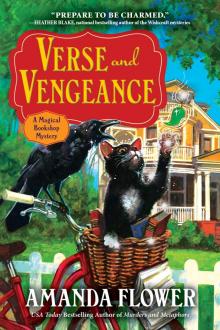

Marshmallow Malice Verse and Vengeance

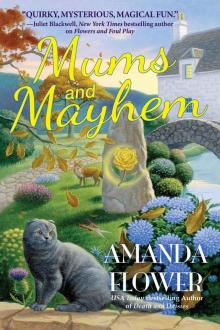

Verse and Vengeance Mums and Mayhem

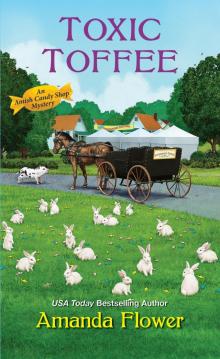

Mums and Mayhem Toxic Toffee

Toxic Toffee Criminally Cocoa

Criminally Cocoa Assaulted Caramel

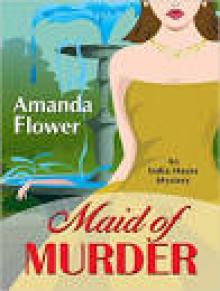

Assaulted Caramel Maid of Murder aihm-1

Maid of Murder aihm-1 Murders and Metaphors

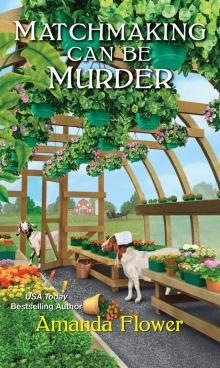

Murders and Metaphors Matchmaking Can Be Murder

Matchmaking Can Be Murder Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery)

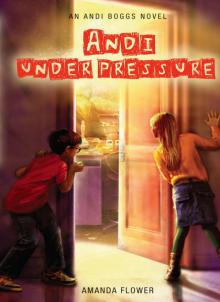

Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery) Andi Under Pressure

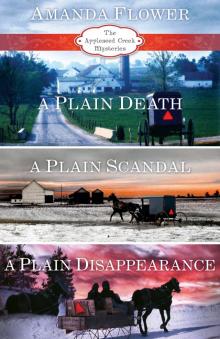

Andi Under Pressure Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3

Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3 A Plain Disappearance

A Plain Disappearance Andi Unstoppable

Andi Unstoppable The Final Vow

The Final Vow A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4)

A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4) The Final Tap

The Final Tap The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery

The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery Andi Unexpected

Andi Unexpected Lethal Licorice

Lethal Licorice Premeditated Peppermint

Premeditated Peppermint Death and Daisies

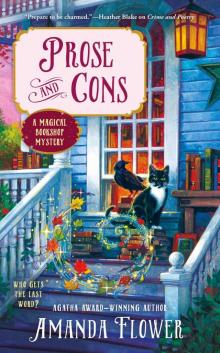

Death and Daisies Prose and Cons

Prose and Cons