- Home

- Amanda Flower

The Final Tap Page 10

The Final Tap Read online

Page 10

“Please call me Robert,” he said.

“And you can call me Kelsey.”

He nodded and examined the visitor center’s main room. “It’s impressive what you’ve accomplished with the Farm in such a short time. I remember coming here when my nephews were small and enjoying it, and it wasn’t half the establishment it is now.”

“Thank you,” I said. “I wouldn’t be able to do it without the generosity of the Cherry Foundation.”

“It was a great loss to the community when Cynthia Cherry passed.”

I simply nodded. Thinking about Cynthia always brought tears to my eyes. I cleared my throat. “Let me show you where you’ll be.”

He adjusted his grip on his briefcase and followed me across the visitor center to the classroom on the opposite side of the building from the dining room.

When I stepped inside, I found Gavin checking the equipment. On a long table there was everything that Stroud would need for his presentation: spiles, filters, and a hydrometer that would measure the sugar content of the maple syrup. The hand drill was missing—it was in the evidence room at the police station. Gavin had replaced it with a battery-operated drill. That would have to do.

Gavin stepped around the table. “Everything you need for the class should be here.”

Stroud walked forward and examined the table’s contents. “This should do nicely. Thank you, Gavin.” He straightened up. “And I’m sorry about how last night’s meeting went. Rest assured that no one at Sap and Spile thinks you had anything to do with Conrad’s death.”

Gavin nodded curtly. “I’d better go get ready for my school visit.” He walked out of the door.

I pointed to the laptop and projector in the corner of the room. “I wasn’t sure if you would be showing a PowerPoint as part of your talk, so I had Benji bring that in. I can set it up for you if you need it.”

He shook his head. “I’m a little old fashioned in that way. I’ll pass out some handouts, and I see you have a whiteboard in the front of the room if I have to write something down for the class to remember.”

I nodded.

At the back of the room there was a table holding thirty copies of Beeson’s book, along with a sign listing a price. Stroud noticed it and frowned. “What are those doing here?”

“I bought them,” I said. “So that Dr. Beeson could have a book signing after the class. Even though he’s gone, I’d still like to get them sold. I think the students in your class will be interested in it.”

Stroud pursed his lips.

Thankfully, any further discussion about the books was interrupted with the arrival of the first students for the course. An elderly couple walked in and beamed. “Is this the tree tapping class?” the woman asked.

“It sure is,” I said.

“Wonderful! I’ve been looking forward to this class for a week. Ken and I have wanted to tap our trees for years. We have six sugar maples on our property. This will be the year that we’re going to do it.” She walked over to the book table in the back of the room. “Oh, I’ve been so looking forward to reading this.” She picked up a copy and looked at Stroud. “Are you the instructor?”

He nodded.

“Can you sign my book before the rest of the class arrives? Ken and I might have to sneak out early to pick up our granddaughter from school. She goes to half-day preschool.” She moved toward Stroud with the book held out in her hand.

Stroud stepped back from her as if she offered him a snake. “I’m so sorry. You’re mistaken. It’s …” His voice caught. “That book is not mine. My name is not on it.”

The woman dropped the book to her side. “But the confirmation email I got said the author of Maple Sugar and the Civil War would be teaching the class.”

“I’m so sorry for the confusion,” I said in my best cruise director voice. “Conrad Beeson, who was going to teach the course and wrote that book, wasn’t available today.”

I winced internally. That was one way to put it.

“Why not?” she asked.

The man, who I assumed was her husband, Ken, put a hand on her shoulder. “You remember, Carol—that’s the professor who died yesterday. I read about it in this morning’s paper. It said that he’d had a heart attack right here on the Farm.”

I bit the inside of my lip and waited to see if Ken would mention anything about murder. I hadn’t been able to check the paper yet to see what the media coverage of Beeson’s death was. I was disappointed that the Farm was mentioned. More bad publicity for my beloved museum. But when Ken didn’t say anything more, I knew the fact that Beeson had been murdered hadn’t been made public. I had a feeling that Ken and Carol would have shared that little fact if they knew about it.

Carol drooped. “What a terrible shame. I really wanted him to sign my book.” She looked to me. “I collect signed copies from authors, you see, and then sell them online. I’ve done very well at it. It’s amazing what people will pay for a bestselling author’s signature.”

Her husband nodded. “It’s a shame. If we’d been able to have it signed before he died, then it might be worth more now that he’s dead.”

Five or six more adults filed into the classroom, and as the sound of children’s voices could be heard in the lobby, I took that as my chance to escape the awkward moment. “If you will excuse me.” I fled the room.

Three dozen children milled around the visitor center, whooping and laughing. Their teachers asked in vain for them to quiet down. I wove through the children and reached Gavin’s side at the doors to the Farm grounds. He looked up from the clipboard that he held. “Looks like I’ll have my hands full today.”

I scanned the room. “I think so.” I glanced outside. The sun was shining and the temp would be in the mid-forties. That was Ohio for you—one day it was the tundra and the next spring was knocking on the door. “The sap might be running today after all.”

He nodded. “I tapped a tree this morning in the sugar grove to test, and it’s running.”

“Great. I’ll let Robert know, so he and the class can tap some trees.”

Gavin nodded.

“Don’t forget, after your school visit we have to check out the sugarhouse in the park,” I added.

His shoulders sagged. “I was hoping you’d forgotten.”

“I don’t forget anything.”

“I know. It’s annoying,” he said.

I laughed. “You’d better start the program.” I inclined my head toward the children in the room. “They’re plotting mutiny.”

He nodded and then put his fingers in his mouth and whistled. The shrill sound brought all conversation in the room to a complete halt.

I rubbed my ear. Sheesh, he could have warned me. I’d need to get my hearing checked after that blast.

I returned to the classroom while Gavin told the kids to line up for a tour of the maple grove. I peeked into the back of the room. The class was full and Stroud was in the middle of his introduction.

“I’ve been maple sugaring since I was a child. It’s a long-running tradition in northeast Ohio, and one that early settlers like the Bartons did in order to make sugar to sweeten their coffee and tea, and to bake with. Since there are so many varieties of sugar today, maple sugar is not as popular for baking as it once was.”

A man with a bald patch on the back of his head spoke up. Since I was in the back of the room, I couldn’t see his face. “So the early settlers discovered maple sugar?”

“Oh, no.” Stroud shook his head and seemed to relax as he warmed up to his subject matter. “The Native Americans were tapping trees long before any white settlers arrived in the Cuyahoga Valley. They would use a hatchet to make a small V-shaped cut into the tree, and then they would take a sturdy piece of bark to make a spile. To boil the water out of the sap to create syrup, they used hot rocks. As you can imagine, that took a lot o

f time, up to three days of constantly heating and changing the rocks. Many of the Native Americans couldn’t wait that long, so they made hard discs out of the maple sugar, and they even used that as currency.”

I slipped out of the room, happy to see Stroud had the class well in hand. I found Benji in the dining room, helping Jayne set the table for the children’s pancake lunch. I was happy to see that the containers of maple syrup were sitting on the counter between the dining room and kitchen and would be distributed by an adult. The less maple syrup spills, the better.

“Benji,” I said.

“What’s up?” she asked.

“Everything seems to be going smoothly with the school visit and the tree tapping class. I’m going to run an errand.”

She set a fork on a placemat. “An errand?” She glanced over at Judy, who was on the opposite side of the room, and lowered her voice as if she didn’t want Judy to overhear. “This wouldn’t have anything to do with Dr. Beeson, would it?”

“Maybe,” I said.

“Kelsey.” Benji stretched my name out into three syllables. She glanced at Judy again. “Gavin told me that the police confirmed Dr. Beeson was murdered.”

I nodded.

She blew out a breath. “Then don’t you think you should stay out of it? Wasn’t what happened last summer enough for you?”

“It was more than enough, but the police think Gavin is behind his death.”

Benji looked as if I’d slapped her. “They do?” she squeaked.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

She set the container of silverware she was holding on the cafeteria table. “Then I think I made it worse for him.”

I wrinkled my brow.

“Detective Brandon was waiting for me outside my apartment last night when I got home from class. She asked me if I knew where Gavin was when Dr. Beeson was killed. I told her that I didn’t.” She sighed. “And I told her that I couldn’t find him when you sent me back to the visitor center to tell him and Judy that we found Dr. Beeson in the woods.” She chewed on her lip. “I shouldn’t have done that.”

I patted her shoulder. “You didn’t do anything wrong. You were honest with the police. I would never ask you to lie.” I paused. “But you can see how it looks bad for Gavin, can’t you? And why I have to help him?”

She nodded. “All right. I’ll handle things while you’re out.”

I thanked her and headed for the exit.

fifteen

After stopping in my office for my coat, I jumped in my car and drove to New Hartford College, the small technical college where my father was a drama professor. The college specialized in courses that dealt with costume, makeup, and set design. They also had a few classes in acting and playwriting, and those were the ones my father had taught for the last thirty years.

It was the middle of the spring semester, and students and faculty made their way across campus. Since the thermometer was approaching forty, a few hardy male students wore shorts. I parked my car as close as I could to the theater building, where crocuses were just beginning to sprout by the front door. Another sign of spring.

I hurried inside and peeked into the large auditorium to make sure I wasn’t interrupting play practice or a class. Dad taught most of his classes in the auditorium itself. He said that actors learned better on the stage than in the classroom.

My boots made an eerie shuffling sound on the brushed velvet carpet. The house lights were down, and only the lights that told me of the many exits were illuminated.

The auditorium was used for college events, but they allowed the town of New Hartford to use the space for town meetings and community events; at a price, of course. The vast open space gave me the creeps much more than the cramped old buildings on Barton Farm ever did.

I hurried down the long aisle and up the steps onto the stage. My father’s office was backstage, tucked away in what was meant to be a dressing room. Office space was a premium on the tiny campus, and that small, windowless room was the best the college could offer him, not that he minded. I couldn’t imagine his office being anywhere else. Whereas it would make me crazy to be isolated from the rest of the campus, it never bothered Dad. He said it made him feel close to his dramatic kindred spirits.

Dad’s office door was open, and yellow light poured out onto the dark backstage area. I knocked on the doorframe.

“Well, hello,” he bellowed. He always spoke as if he were projecting his booming stage voice. As well as being a professor, Dad was also an active participant in local community theater, a regular scene stealer on the New Hartford community stage. “I have to say I’m surprised to see you here. I thought you would be back at the Farm preparing for the weekend.” He rested his hands on his round belly as if it were a shelf. “I’m looking forward to my stack of pancakes doused in maple syrup. I hope you’ll save your father a few extra servings.”

“There’ll be plenty for everyone,” I said with a smile, stepping into the cramped space. “Alice bought enough pancake fixings to serve the Roman army.”

He grinned. “Good to know.”

I sat in an uncomfortable wooden chair across from him. Piles of books, notebooks, and papers stood in precarious stacks on his desk. There was also a pile of plays that he was reading. My office back at Barton Farm didn’t look much better. Like father, like daughter. We had no grasp on organizing paper. Thankfully most of my files were digital now, which was so much easier. “What are you working on?”

“I was just doing a little grading. I have a great crop of student players this year. I hope several of them go on to four-year colleges for their BFAs. I was thinking of putting on a showcase at the end of the semester. I just have to convince my department chair and the academic dean.” He wrinkled his nose at the thought. Dad had never been one for college politics. He set the student play he was reading aside. “But I always have time for my favorite child.”

“I’m your only child,” I said with a smile.

“I know. What a blessing that is, so I don’t have to choose a favorite. That must be awkward for a parent.”

I leaned back in the chair. “Parents are supposed to love all their children equally.”

He shrugged. “So they say.”

I shifted in my chair.

Dad pulled the pillow out from behind him. “Here. It might make it a little more tolerable. I’ve been asking the college for new office furniture for years. Now they’re just waiting for me to retire.”

“You’ll never retire.”

He grinned. “You’re right. That’s one of the perks of tenure. I don’t leave until I say so. I wish they’d just accept that and give me a new desk.” He leaned back in his own chair. “You never just drop in for a visit. What’s going on?” His eyebrows knit together. “Is Hayden all right?”

“Hayden’s perfectly fine.” I paused. “There was an incident on the Farm yesterday.”

He perked up. “Oh?”

“With Dr. Beeson.”

He blinked. “The horticulture professor?”

I nodded. “He was hurt. Well, more than hurt.”

Dad scratched his chin. “I suppose I should come out of my cave more often to know what the news is on campus. How is he?”

I frowned. “That’s the problem. He died.”

Dad’s eyes grew two sizes behind his glasses. “Died? How?”

I went on to tell him everything that happened since the moment Dr. Beeson left Benji and me alone in the woods. “The police believe he had a heart attack and then someone stabbed him with his drill after he fell. He was trying to tell me something before the paramedics arrived.”

“Did you ask them to find out what he was trying to say?” Dad leaned across the desk.

I shook my head. “No. I wish I had. He was in so much pain, and the EMTs had to help him if they could. There was a chance they m

ight have been able to save his life, even if it was a slim one at best.”

Dad fell back in his chair. “How sad. I didn’t know Conrad well. We’d see each other occasionally at meetings and campus-wide events, but the horticulture and animal husbandry departments are sort of off by themselves. You can’t even walk to their offices. You have to drive.” He paused. “Was Chase one of the paramedics that came out?”

“He was.” I tried to keep my voice as even as possible. There was no way I was going to tell my father that Chase came to the cottage last night, even though his visit had been completely innocent and related to the murder. Laura and my father were both in the same camp to find me a new boyfriend. The pair of them had redoubled their efforts to set me up with a guy ever since Eddie had announced his engagement to Krissie. I was perfectly happy with my life. I had Hayden and the Farm. I didn’t have much time for anything or anyone else. If I chose to date again, it would be up to me, not them.

“Chase is such a nice young man, and he admires you,” Dad said, confirming my suspicions.

I frowned. “Can we talk about the dead man?”

Dad sighed. “All right. So you plan to find out what happened?”

I nodded and told him about Gavin’s involvement in the case.

Dad clicked his tongue. “That’s too bad. Gavin is a nice young man too. I’ve always liked him.”

“I know, and I have to help him. I’m certain he didn’t do anything wrong.” I paused. “I mean, announcing to an entire room of Sap and Spile members that he wanted Beeson dead wasn’t the best idea in the world. But he’d never go through with it. I just have to convince Detective Brandon that that’s true.”

“That’s your mother in you talking,” Dad said. “She was a crusader too.” His face drooped and for the first time since I’d arrived, he looked his full sixty-seven years. “God rest her soul.”

My mother had been the love of my father’s life. He hadn’t even looked at another woman since she died, although he had a long list of widowed admirers. There was no one who could take mom’s place in his heart. If I admitted it, it was something I’d wanted in my own life. I thought I had found it when I married Eddie, but I’d been wrong. Now I didn’t know if I would ever find it. I knew Chase had a crush on me, but as flattering as that was, it wasn’t the same as undying love.

Marshmallow Malice

Marshmallow Malice Verse and Vengeance

Verse and Vengeance Mums and Mayhem

Mums and Mayhem Toxic Toffee

Toxic Toffee Criminally Cocoa

Criminally Cocoa Assaulted Caramel

Assaulted Caramel Maid of Murder aihm-1

Maid of Murder aihm-1 Murders and Metaphors

Murders and Metaphors Matchmaking Can Be Murder

Matchmaking Can Be Murder Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery)

Maid of Murder (An India Hayes Mystery) Andi Under Pressure

Andi Under Pressure Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3

Appleseed Creek Trilogy, Books 1-3 A Plain Disappearance

A Plain Disappearance Andi Unstoppable

Andi Unstoppable The Final Vow

The Final Vow A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4)

A Plain Malice: An Appleseed Creek Mystery (Appleseed Creek Mystery Series Book 4) The Final Tap

The Final Tap The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery

The Final Reveille: A Living History Museum Mystery Andi Unexpected

Andi Unexpected Lethal Licorice

Lethal Licorice Premeditated Peppermint

Premeditated Peppermint Death and Daisies

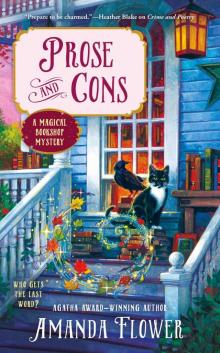

Death and Daisies Prose and Cons

Prose and Cons